MORE COVERAGE

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

Introduction - Understanding Islam through Hadis - Religious Faith or Fanaticism

Islam is not merely a theology or a statement about Allah and his relationship with His creatures. Besides containing doctrinal and creedal material, it deals with social, penal, commercial, ritualistic, and ceremonial matters. It enters into everything, even into such private areas as one's dress, marrying, and mating. In the language of the Muslim theologians, Islam is a complete and completed religion.

It is equally political and military. It has much to do with statecraft, and it has a very specific view of the world peopled by infidels. Since most of the world is still infidel, it is very important for those who are not Muslims to understand Islam.

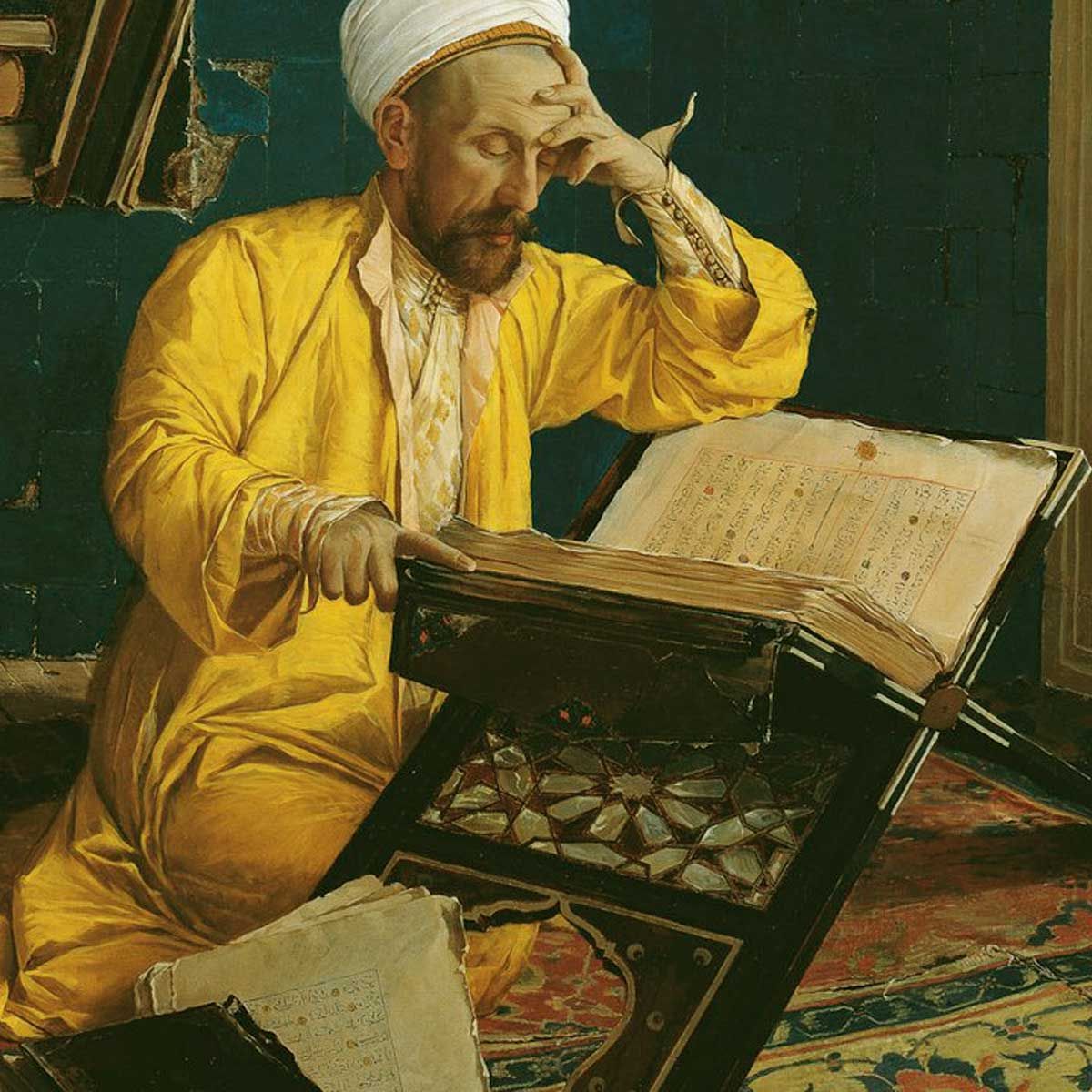

The sources of Islam are two: the Quran and the hadiths (Sayings or Traditions), usually called the Sunnah (customs), both having their center in Muhammad. The Quran contains the Prophet's revelations (wahy); the hadiths, all that he did or said, or enjoined, forbade or did not forbid, approved or disapproved. The word hadiths, singular in form (pl. ahadis), is also used collectively for all the traditions taken together, for the whole sacred tradition.

Muslim theologians make no distinction between the Quran and the hadiths. To them, both are works of revelation or inspiration. The quality and degree of the revelation in both works are the same; only the mode of expression is different. To them, the hadiths are the Quran in action, the revelation made concrete in the life of the Prophet. In the Quran, Allah speaks

through Muhammad; in the Sunnah, He acts through him. Thus Muhammad's life is a visible expression of Allah's utterances in the Quran.

God provides the divine principle, Muhammad the living pattern. No wonder, then, that Muslim theologians regard the Quran and the hadiths as being supplementary or even interchangeable. To them, the hadiths are wahy ghair matlu (unread revelation, that is, not read from the Heavenly Book like the Quran but inspired all the same); and the Quran is hadiths mutawatir, that is, the Tradition considered authentic and genuine by all Muslims from the beginning.

Thus the Quran and the hadiths provide equal guidance. Allah with the help of His Prophet has provided for every situation. Whether a believer is going to a mosque or his bedroom or the toilet, whether he is making love or war, there is a command and a pattern to follow. And according to the Quran, when Allah and His Apostle have decided a matter, the believer does not have his or her own choice in the matter (33:36).

Though the non-Muslim world is not as familiar with the Sunnah, or hadiths, as with the Quran, the former even more than the latter is the most important single source of Islamic laws, precepts, and practices. Ever since the lifetime of the Prophet, millions of Muslims have tried to imitate him in their dress, diet, hairstyle, sartorial fashions, toilet mores, and sexual and marital habits. Whether one visits Arabia or Central Asia, India or Malaysia, one meets certain conformities, such as the veil, polygamy, ablution, and istinja (abstersion of the private parts). These derive from the Sunnah, reinforced by the Quran. All are accepted not as changing social usages but as divinely ordained forms, as categorical moral imperatives.

The subjects that the hadiths treat are multiple and diverse. It gives the Prophets views of Allah, of the here and the hereafter, of hell and heaven, of the Last Day of Judgment, of Iman (faith), salat (prayer), zakat (poor tax), sawm (fast), and hajj (pilgrimage), popularly known as religious subjects; but it also includes his pronouncements on Jihad (holy war), al-anfal (war booty), and khums (the holy fifth); as well as on crime and punishment, on food, drink clothing, and personal decoration, on hunting and sacrifices, on poets and soothsayers, on women and slaves, on gifts, inheritances, and dowries, on the toilet, ablution, and bathing; on dreams, and medicine, on vows and oaths and testaments, on images and pictures, on dogs, lizards, and ants.

|

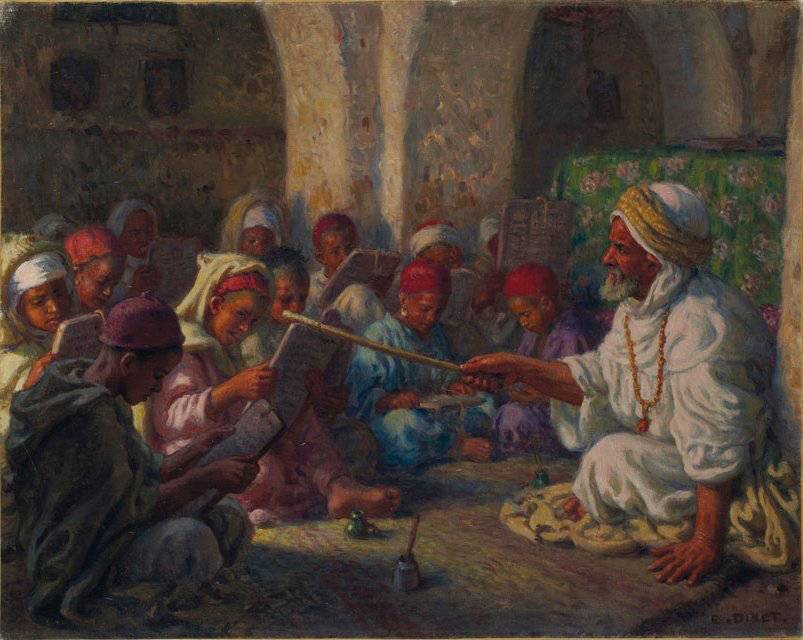

The hadiths constitute voluminous literature. It gives even insignificant details of the Prophet's life. Every word from his lips, every nod or shake of his head, every one of his gestures and mannerisms was important to his followers. These are remembered by them as best as they could and passed on from generation to generation. Naturally, those who came into greater contact with the Prophet had the most to tell about him. Aisha, his wife, Abu Bakr, and Umar, his aristocratic followers, Anas b. Malik, his servant for ten years, died at the ripe age of 103 in A.H. 93, and Abdullah b.

Abbas, his cousin, were fertile sources of many ahadis. But another most prolific source was Abu Huraira, who is the authority for 3,500 traditions. He was no relation to the Prophet, but he had no particular work to do except that he specialized in collecting traditions from other Companions. Similarly, 1,540 traditions derive from the authority of Jabir, who was not even a Quraish but belonged to the Khazraj tribe of Medina, which was allied to Muhammad.

Every hadith has a text (matn) and a chain of transmission (isnad). The same text may have several chains, but every text must be traced back to a Companion (as-hab), a man who came into personal contact with the Prophet. The Companions related their stories to their successors (tabiUn), who passed them on to the next generation.

At first, the traditions were orally transmitted, though some of the earliest narrators must have also kept written notes of some kind. But as the Companions and the Successors and their descendants died, a need was felt to commit them to write. There were two other reasons. The Quranic injunctions were probably sufficient for the uncomplicated life of the early Arabs, but as the power of the Muslims grew and they became the masters of an extended empire, they had to seek a supplementary source of authority to take into account new situations and new customs. This was found in the Sunnah, in the practice of the Prophet, already very high in the estimation of the early Muslims.

There was an even more pressing reason. Spurious traditions were coming into being, drowning the genuine ones. There were many motives at play behind this development. Some of these new traditions were merely pious frauds, worked up to promote what the fabricators thought were elements of a pious life, or what they thought were the right theological views.

There were also more personal motives at work. The traditions were no longer mere edifying stories. They were sources of prestige and profit. To have one's ancestors counted among the Emigrants or Helpers, to have them present at the Pledge of al-Aqabah or included among the combatants at the Battles of Badr and Uhud-in short, to have them mentioned in any context of loyalty and usefulness to the Prophet-was a great thing. So Traditionists who could get up right traditions were very much in demand. Traditionists

like ShurahbIl b. Sad utilized their power effectively; they favored and blackmailed as it suited them.

Spurious traditions also arose to promote factional interests. Soon after Muhammad's death, there were cutthroat struggles for power between several factions, particularly the Alids, the Ummayads, and later on the Abbasids. In this struggle, great passions were generated, and under their influence new traditions were concocted and old ones usefully edited.

The pious and the hero-worshipping mind also added many miracles around the life of Muhammad, so that the man tended to be lost in the myth. Under these circumstances, a serious effort was made to collect and sift all the current traditions, rejecting the spurious ones and committing the correct ones to write. A hundred years after Muhammad, under Khalifa Umar II, orders were issued for the collection of all extant traditions under the supervision of Bakr ibn Muhammad. But the Muslim world had to wait another hundred years before the work of sifting was undertaken by a galaxy of traditionists like Muhammad Ismail al-Bukhari (A.H. 194-256=A.D. 810-870), Muslim ibnul-Hajjaj (A.H. 204-261=A.D. 19-875),

Abu Isa Muhammad at-TirmizI (A.H. 209-279=A.D. 824-892), Abu Daud as-Sajistani (A.H. 202-275 = A.D. 817-888) and others.

Bukhari laid down elaborate canons of authenticity and applied them with a ruthless hand. It is said that he collected 600,000 traditions but accepted only 7,000 of them as authentic. Abu Daud entertained only 4,800 traditions out of a total of 500,000. It is also said that 40,000 names were mentioned in different chains of transmission but that Bukhari accepted only 2,000 as genuine.

As a result of the labor of these Traditionists, the chaotic mass was cut down and some order and proportion were restored. Over a thousand collections, which were in vogue died away in due course, and only six collections, the Sihah Sitta as they are called, became authentic SahIs, or collections. Of these, the ones by Imam Bukhari and Imam Muslim are at the top-the two authentics, they are called. There is still a good deal of the miraculous and the improbable in them, but they contain much that is factual and historical. Within three hundred years of the death of Muhammad, the hadiths acquired substantially the form in which it is known today.

To the infidel with his critical faculty still intact, the hadiths are a collection of stories, rather unedifying, about a man, rather all too human. But the Muslim mind has been taught to look at them in a different frame of mind. The believers have handled, narrated, and read them with a feeling of awe and worship. It is said of Abdullah ibn Masud (died at the age of seventy in A.H. 32), a Companion and a great Traditionist (authority for 305 traditions), that he trembled as he narrated hadiths, sweat often breaking out all over his forehead. Muslim believers are expected to read the traditions in the same spirit and with the same mind. The lapse of time helps the process. As the distance grows, the hero looms larger.

We have also chosen the Sahih Muslim as the main text for our present volume. It provides the base, though in our discussion we have often quoted from the Quran. The Quran and the hadiths are interdependent and mutually illuminating. The Quran provides the text, the hadiths the context.

The Quran cannot be understood without the aid of the hadiths, for every Quranic verse has a context, which only the hadiths provide. The hadiths give flesh and blood to the Quranic revelations, reveal their more earthly motives, and provide them with the necessary locale.

Until now only partial English translations of some hadiths collections were available.

|

Now a word about how the present volume came to be written. When we read Dr. Siddiqi's translation, we felt that it contained important material about Islam which should be more widely known. Islam, having been dormant for several centuries, is again on the march. Even before the Europeans came on the scene, the Muslims had their variation of the white man's burden of civilizing the world. If anything, their mission was even more pretentious for it was commanded by Allah Himself. Muslims wielded their swords to root out polytheism, dethrone the gods of their neighbors, and install in their place their godling, Allah.

These were accidental terrestrial rewards for disinterested celestial laborers. Thanks to the new oil wealth of the Arabs, the old mission is being revived. A kind of Muslim Cominform is taking shape in Jidda. The oil-rich Arabs are assuming responsibility for Muslims everywhere, looking after their spiritual needs as well as their more temporal interests. Their money is active throughout the Muslim world, in Pakistan and Bangladesh, in Malaysia, Indonesia, and even India, with a large Muslim population.

The Arabs are still militarily weak and dependent on the West, but the full fury of their interference is to be seen in countries of Asia and Africa which are economically poor and ideologically weak. Here they work from the bottom as well as from the top. They buy local politicians. They have bought the conversion of the presidents of Gabon and the Central African Empire. They have adopted the Muslim minorities of Darul Harb, i.e., infidel countries which have not yet been fully subdued by Muslims. They are using these minorities to convert these countries into Darul Islam, or countries of peace, i.e., countries where Islam dominates.

Even in the best of circumstances, it is difficult to assimilate Muslim minorities into the national mainstream of a country. Arab support has made the task still more difficult. It was this support that was behind the rebellion of the Moro Muslims in the Philippines. In India, there is a continuing Muslim problem that refuses solution despite the division of the country. Arab interference has complicated matters still further.

The Sahih Muslim, like other hadiths collections, also gives very intimate glimpses of the life of the Prophet, an impressionistic view that makes him seem more a living, breathing person than the portrayals given in his more formal biographies. Here one comes to know him, not through his pompous deeds and thoughts, but his more workaday ideas and actions. There is no makeup, no cosmetics, no posturing for posterity. The Prophet is caught as it were in the ordinary acts of his life-sleeping, eating, mating, praying, hating, dispensing justice, planning expeditions, and revenge against his enemies. The picture that emerges is hardly flattering, and one is left wondering why in the first instance it was reported at all and whether it was done by his admirers or enemies. One is also left to wonder how the believers, generation after generation, could have found this story so inspiring.

It was in this way and by this logic that Muhammad's opinions became the dogmas of Islam and his habits and idiosyncrasies became moral imperatives: Allah's commands for all believers in all ages and climes to follow.

Chapters

- Introduction - Understanding Islam through Hadis - Religious Faith or Fanaticism

- Iman - Understanding Islam through Hadis - Religious Faith or Fanaticism

- Purification - Understanding Islam through Hadis - Religious Faith or Fanaticism

References:

Understanding Islam through Hadis - Religious Faith or Fanaticism? - Ram Swarup - Exposition Press | Smithtown, New York

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- Iman - Understanding Islam through Hadis - Religious Faith or Fanaticism

- Why authorities ignoring conspiracy of Sexual objectification of Hindu women: #Hslut4Mstud Users on Reddit, Twitter and Tumblr are targeting Hindu women with pornographic content ‘for Muslim studs’

- Hero of Pawankhind: Veer Maratha Bajiprabhu Deshpande, who led 300 Soldiers against 12000 Adilshahi Army defending Shivaji

- From changing Muslim identity for luring Hindu girls to black magic, mysterious water in dargahs and sexual exploitation: Grooming jihad horrors from the back of beyond of Gujarat

- Supreme Court allows same Muslim brothers to rent temple properties who have wrecked mayhem in Srisailam temple

- Bajrang Dal's peaceful rally in Mewat (mini Pakistan) is painted panic mongering by Islamist Media

- Congress-Left corporal commination, BJP’s moment of convenience: Mainstreaming the ‘Nationalist Muslim’ with the reinstallation of Hindutva

- Devkinandan Thakur's statement is a slap in the face of the Islamist hoodlum from Hyderabad - “Many more Yogis and Modis standing in line…”

- Mohammedan needs to 'take back Babri Masjid', ISIS magazine states that Hindus are ‘filthy urine drinkers’ who learned civilized living from Muslims

- Jihad Recruitment going on in Madrassas forced the Assam government to cease hundreds of them

- Actor Urfi Javed admits that most hate she receive is from Muslims, confirms that she doesn’t believe in Islam and will never marry a Muslim man

- Story of Hamid Dalwai, a man who started the triple talaq movement, and why it is impossible to reform Islam: Objects of criticism include the morality of the life of Muhammad, the founder of Islam

- Busting the myth of “glories” of the Mughal Empire and its economic superiority as fantasized by Indian Marxist and Liberal historians

- Due to ASI negligence Muslim encroachers squat on ancient Raja Yayati Fort in Kanpur

- Dewan Bahadur saheb was made to quit as a Speaker because he wasn't a Muslim: Tragedy of a Christian leader who backed Pakistan’s creation