More Coverage

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Join Satyaagrah Social Media

In just 8 years, a forgotten warrior carved through Ladakh, Baltistan, and even Tibet with 6,000 men—his name was General Zorawar Singh, and though he fell in 1841 at Toyo, his sword drew the borders we still live by; a hidden tale buried in Himalayan ice

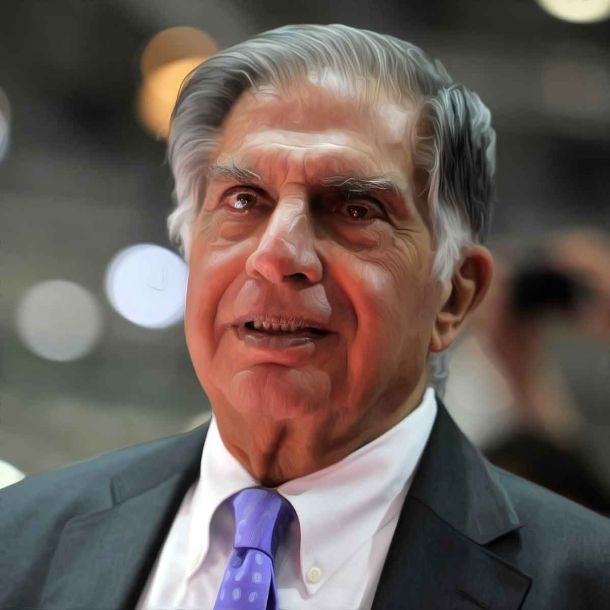

In the chill valleys of the Himalayas, where oxygen thins and snow never seems to melt, one man dared to imagine a frontier that would expand beyond mountains and borders. That man was General Zorawar Singh Kahluria (1786–1841), a name etched in the history of India as one of the greatest military minds of the 19th century. Born into a Chandel Rajput family in the princely state of Kahlur (present-day Bilaspur, Himachal Pradesh), Zorawar’s journey began far from royalty and privilege. His early life was marked by struggle – “a family feud forced him to flee his village, and he received no formal education.” But fate often smiles upon those with unshakable resolve.

As a youth, Zorawar found his way into the service of Raja Jaswant Singh in Jammu, where he honed his skills in horsemanship and weaponry. It was here that he first displayed the spark of leadership. His potential did not go unnoticed. The rising Dogra leader, Raja Gulab Singh, a trusted vassal under Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s Sikh Empire, soon discovered Zorawar’s talent. Starting humbly as a sepoy in the Reasi fort garrison, Zorawar quickly made an impression by “devising a more efficient supply system, impressing Gulab Singh.”

His dedication and innovation earned him rapid promotions. He rose to become Kiladar (fort commander) of Reasi, and later Inspector of Commissariat for all forts north of Jammu. In 1823, his growing stature led Gulab Singh to appoint him Wazir (governor) of the newly-conquered Kishtwar, a province bordering Ladakh. This crucial appointment gave Zorawar both military authority and administrative experience, as well as a strategic position to train his troops and plan forward operations. By the early 1830s, Zorawar wasn’t just a commander; “he commanded a personal battalion of 875 men and had won Gulab Singh’s full confidence.” The Himalayan winds had begun to whisper his name.

|

The Ladakh Campaign: A Kingdom in the Clouds (1834–1835)

In 1834, destiny knocked in the form of a political feud in Ladakh. Then an independent kingdom nestled in the Himalayas, Ladakh was a prize eyed by many, thanks to its lucrative pashmina wool trade and its unique position between Punjab, Tibet, and Central Asia. A local feud broke out when “the Raja of Timbus, a Ladakhi vassal, sought Dogra help against his overlord, King Tsepal Namgyal of Ladakh.” For Raja Gulab Singh, this was the perfect moment. Along with glory, this campaign also promised much-needed revenue to offset the recent drought in Kishtwar. Thus, he turned to his trusted general.

Zorawar didn’t hesitate. He organized a formidable high-altitude fighting force, estimated at 5,000–10,000 soldiers, with a core of battle-hardened troops from Jammu and Himachal. As the spring of 1834 melted the snow, Zorawar led his troops east from Kishtwar, traversing snow-covered mountain passes into the Suru Valley of Ladakh. The Dogra invasion officially began, and the first clash came on 16 August 1834, at Sankoo on the banks of the Suru River. There, Zorawar’s soldiers “stormed a Ladakhi hill fort” in freezing conditions. After a fierce battle, the Dogras emerged victorious. But unlike many conquerors, Zorawar took a clever route. “Rather than pillaging, Zorawar ordered his men to spare local crops” – a decision that won the hearts of the Ladakhi villagers and secured a much-needed food supply for his forces.

By mid-September 1834, Zorawar had moved to Pushkyum (Paskyum) near Kargil, where the Ladakhi army had regrouped. Another long and bloody battle broke out. The Dogras, undeterred, fought bravely and eventually broke through the resistance. The remaining Ladakhi soldiers fled to the fort of Sod, only to face the wrath of Mehta Basti Ram, Zorawar’s courageous lieutenant. Leading 500 men under artillery fire, Basti Ram captured the fort, along with hundreds of prisoners. As winter approached, Zorawar tried diplomacy – offering to withdraw if Ladakh paid a one-time ₹15,000 indemnity. But King Tsepal Namgyal refused. Instead, he raised “22,000 troops” and launched a massive counterattack in late 1834, forcing the Dogras back to Langkartse in the Suru Valley. There, trapped in the snow, Zorawar’s men endured “a harsh winter blockade”. Yet the Ladakhi army hesitated – wary, perhaps, of the Dogras’ famed mountain warfare.

When spring thawed the frozen battlefields, Zorawar struck again. In April 1835, he led a surprise dawn attack on the Ladakhi camp at Langkartse, completely catching the enemy off-guard. The result was a devastating Dogra victory. The tide had turned. By summer 1835, the Dogras had “recaptured all lost ground” and advanced to Lamayuru, a key monastery town, where Zorawar set up his forward headquarters. Realizing he was outmatched, King Tsepal Namgyal sued for peace.

The treaty that followed was firm: “The Gyalpo (king) could remain on his throne but as a vassal of Gulab Singh.” Ladakh was to pay ₹50,000 as war indemnity and ₹20,000 in annual tribute to Jammu. To make sure the king kept his word, Zorawar stationed a Dogra representative, Munshi Daya Ram, in the capital Leh. By late 1835, Zorawar Singh had effectively annexed Ladakh into the Dogra domain – a victory so resounding that it earned him the celebrated title: “Conqueror of Ladakh.”

|

Securing the Summit: Dogra Consolidation (1836–1840)

Though victory in Ladakh was complete, peace would not come easily. The new Dogra rule upset local power structures and ignited fresh political tension – both inside Ladakh and back in Lahore, the heart of the Sikh Empire. In early 1836, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, wary of Gulab Singh’s growing power, summoned Zorawar to Lahore to answer for the unilateral conquest. Zorawar stood firm. “He justified that his conquest had expanded the Sikh Empire’s frontiers,” calming royal tempers. But then came the shocker: “he even boldly proposed carrying the empire’s standard beyond Ladakh into Tibet and China.” This startled Ranjit Singh, who turned down the idea at the time – but the seed of Tibet had been planted in Zorawar’s ambitious mind.

Even before the echoes of that proposal faded, rebellion stirred again. Mehan Singh, the jealous Sikh governor of Kashmir, secretly encouraged King Tsepal Namgyal to rise once more. In 1837, the king rebelled. Zorawar, hearing of the defiance, rushed back to Leh through difficult terrain. His return was enough – the intimidated king “immediately surrendered and begged forgiveness.” Zorawar took no chances: he punished the king with another indemnity and replaced him with a more loyal figure, the noble Ngorub Stanzin, whom he placed on the throne. Satisfied, Zorawar returned to Jammu.

But 1838 brought another betrayal. Ngorub, now seated in power, turned against the Dogras. Zorawar had to return – this time in the heart of winter, through the treacherous Zanskar route. He removed Ngorub and reinstated Tsepal Namgyal, who now seemed the lesser of two evils. Still, peace remained elusive. In 1839, Ngorub and some disaffected Ladakhi nobles sparked yet another rebellion. Zorawar, for the fourth time, led a campaign to Leh, crushed the resistance, and captured the ringleaders.

Then came 1840. The last spark of defiance came from Sukamir of Purig, a district in western Ladakh. This time, Zorawar’s response was not patient. “His fifth and final punitive foray into Ladakh ‘brutally suppressed’ the rebellion.” With that, Ladakh’s fate was sealed. The mountains finally fell silent under Dogra rule.

With the gunpowder fading, Zorawar turned from warrior to statesman. Having witnessed the cost of unsteady rule, he took real steps to integrate Ladakh into the Dogra fold. His soldiers and engineers built roads, bridges, and tracks, making the difficult terrain more accessible. The famed British explorer Alexander Cunningham, who visited in the 1840s, noted how these improvements “greatly facilitated trade and travel in Ladakh and Baltistan.” Under Dogra authority, the age-old raids between Ladakhis and Baltis came to an end, replaced by cautious peace and commerce. Slowly, even the mountain folk began to accept the new order – one that brought security, stability, and a reliable road to the future.

The Snowbound Thunder: Zorawar Singh’s Daring Campaigns in Baltistan and Tibet

With the echoes of rebellion in Ladakh finally silenced, Zorawar Singh, now a seasoned and fearless commander, turned his attention toward the frozen and formidable lands of Baltistan. Situated north of Ladakh and west of Tibet, Baltistan was not just a territory of interest—it was a buffer that could secure the Dogra Empire’s vulnerable flanks. This region, known today as part of Gilgit-Baltistan, had long been predominantly Muslim and historically tangled in sporadic wars with Ladakh. For Zorawar, the logic was simple and strategic: “it would secure the Dogra Empire’s flank and end the threat of Baltis aiding Ladakhi rebellions.”

An internal dynastic conflict in Baltistan’s chief kingdom, Skardu, presented the perfect opening. Crown prince Mohammad Shah, who had been at odds with his father, Raja Ahmad Shah, had secretly approached Zorawar for assistance as early as 1835. However, Zorawar, then immersed in subduing Ladakh, had postponed intervention. But by late 1839, everything had aligned in Zorawar’s favor. “Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s death in 1839 meant the Lahore Durbar was too distracted to restrain Dogra expansion.” Moreover, the British East India Company, ever wary of entering remote and harsh territories, paid no heed to Baltistan. With the political coast clear, Gulab Singh gave Zorawar Singh the go-ahead to invade Baltistan, a move that would soon become “one of the most audacious winter campaigns in Indian military history.”

In the bitter December of 1840, Zorawar led an army of approximately 15,000 troops, bolstered by Ladakhi levies, into the snow-clad mountains of Baltistan. His men rode on hardy hill ponies supplied by the Ladakhis, navigating the treacherous terrain of the Karakoram range during the heart of winter. In a feat of unmatched bravery, Zorawar achieved the impossible in early 1841—“a surprise crossing of the Indus River, marching his soldiers over the frozen ice to flank the Balti defenders.” It was a masterstroke. The Skardu forces were caught completely off-guard. Blending swift cavalry charges and infantry tactics, the Dogras smashed through the enemy lines, leaving the Balti army in ruins.

Defeated and desperate, Raja Ahmad Shah sought refuge in the mighty Skardu Fort, perched high and guarded on three sides by the Indus. The fort, long considered impregnable, stood atop a steep, narrow ascent and was stocked with provisions for a long siege. But Zorawar knew no walls too high. He encircled the fortress, and in a move of sheer tactical genius, “cut off its water supply from the Indus.” The siege didn’t last long. The starving garrison surrendered, and by spring 1841, “Ahmad Shah surrendered unconditionally.” With the heart of Baltistan under his boot, Zorawar deposed Ahmad Shah and installed Mohammad Shah as ruler of Skardu, under Dogra suzerainty. The agreement was clear—“Mohammad Shah would pay an annual tribute of ₹7,000 to Jammu.”

Yet, for Zorawar, victory was never partial. He dispatched columns to assert control over the outlying Balti states: Kharmang, Shigar, Khaplu, Rondu, Tolti, and Astor. All wisely chose to submit and pay tribute. Even the distant regions of Gilgit and Hunza, deep in the Gilgit Valley, bowed without resistance. By mid-1841, “Zorawar Singh had effectively brought the entire Gilgit–Baltistan region under Gulab Singh’s control.” The Dogra flag now fluttered from Kargil and Dras in the west to the headwaters of the Indus in the north. These triumphs significantly widened the Dogra map—“a fact that worried both the Lahore Durbar and the British, as Dogra influence crept closer to Tibet and Central Asia.”

|

The Roof of the World: Tibet Expedition and the Final Stand (1841)

Fresh from his conquests, Zorawar now turned his eyes toward an even more formidable challenge: Western Tibet, also known as Ngari Khorsum. This mission was both economically and strategically vital. “Control of western Tibet would safeguard the pashmina wool trade,” which was threatened as Tibetan authorities began bypassing Dogra-controlled Ladakh by routing trade directly to British India through Himachal. This maneuver was undercutting Kashmir’s shawl industry—a key Dogra economic asset. Zorawar responded with authority. He invoked an old Ladakhi claim on parts of Ngari and demanded that Tibet’s Garpon at Gartok send pashm wool only to Ladakh and pay tribute. The Tibetans refused.

At the same time, Gulab Singh, eager to extend his reach and perhaps counter any British ambitions in the Trans-Himalayan region, secured formal approval. “By early 1841, permission was obtained from the new Sikh monarch in Lahore (Maharaja Sher Singh) to undertake this northern expedition,” since it did not violate Sikh-British treaties. What followed was a campaign that would stretch the limits of human endurance. “Zorawar Singh embarked on what would be his final campaign – an epic march across the roof of the world.”

In May 1841, Zorawar led 5,000–6,000 men, composed of Dogra soldiers, Ladakhi, and Balti auxiliaries, across the towering Himalayas. The army moved in three columns: one under a Ladakhi prince along the Indus River, another led by Ghulam Khan through the Kailash ranges, and the third—the largest—under Zorawar himself, cutting across the plateaus south of Pangong Tso. At a staggering 15,000-foot altitude, Zorawar's force defied nature and crushed the few Tibetan outposts in their path. On 5 June 1841, “they captured Rutog with little resistance.” The strategic hub of Gar (Gartok) soon fell, securing the wool trade centers. Pressing deeper, the Dogras reached Lake Manasarovar, the sacred source of the Indus, and advanced to Taklakot (Burang) near Nepal’s border.

Though the Tibetans rushed a general named Pishi to intercept, “they were easily brushed aside.” On 6 September 1841, “Zorawar Singh stormed and seized the fort of Taklakot, completing the conquest of Ngari province.” In just a few months, “the Dogras had overrun roughly 550 miles of Tibetan territory.”

Zorawar then switched to governance. He fortified key locations like Rutog, Gartok, Tsaparang, and Taklakot, stationing Dogra troops and allowing cooperative Tibetan officials to continue under Dogra supervision. His top priority remained clear: “to ensure the flow of pashm wool to Kashmir continued unabated.” By autumn 1841, the Dogra banner flew high over western Tibet. Even envoys from Lhasa and Nepal arrived at Taklakot to negotiate. But his breathtaking advance did not go unnoticed. The British, alarmed at the Dogras’ proximity to Nepal and Tibet, pressured the Lahore Durbar to call back Zorawar. More critically, Tibet, backed by Qing China, began preparing to retake their land. They waited wisely, not confronting him in summer—but letting the winter do the fighting.

And winter arrived, swift and merciless. As late 1841 set in, Zorawar’s situation worsened. “The high passes were choked with snow, cutting off his 450-mile supply line back to Ladakh.” Food and supplies dwindled. “Many Dogra soldiers suffered frostbite, losing fingers and toes; others succumbed to pneumonia and exhaustion.” The horses died, crippling the cavalry. “To stay warm, men burned the wooden stocks of their own muskets as firewood.”

The Tibetans, seeing weakness, advanced with force. In November 1841, “a reinforced Tibetan–Chinese army (about 10,000 strong)” approached. Two Dogra detachments were wiped out. But Zorawar refused to retreat. With his remaining troops, “now reduced to a few thousand weary men,” he made a last stand at Toyo (Toyoor), near Taklakot.

The final chapter began on 10 December 1841, under blizzard conditions. For two days, the Battle of To-Yo raged. Then, on 12 December, Zorawar led a bayonet charge into enemy lines. “A Tibetan matchlock ball struck his shoulder,” yet he pressed on. “Legend says he cried out that either the Tibetans would take his head or he would take his own life – vowing never to retreat.” Moments later, “a Tibetan lancer charged through the melee and impaled Zorawar Singh through the chest with a spear, unhorsing him.” He fell—“mortally wounded.” The enemy then beheaded him and paraded his head as a trophy. The loss of their fearless general shattered Dogra morale. “Many soldiers fled into the mountains only to die of cold, while hundreds were captured by the Tibetans.” And so, “on that fateful 12th of December 1841, ended the saga of Zorawar Singh’s conquests.”

|

The Treaty of Chushul: A War’s Quiet End (1842)

In the wake of Zorawar’s fall, the Dogra survivors staggered back to Ladakh. The Tibetans, emboldened, pushed into Ladakh in early 1842, but Dogra reinforcements from Jammu blocked them. Neither army wanted more bloodshed. Eventually, “a treaty was signed on 17 September 1842 at Leh, restoring the status quo.” Both powers agreed to “honor the old boundaries – Ladakh and Baltistan would remain with Gulab Singh, and the Tibetans would retain their territory beyond the frontier.” Each pledged peace. “This Treaty of Chushul (1842) formally ended the Dogra-Tibetan War.” It also “marked the first formal demarcation of the Ladakh-Tibet boundary that endures to this day.”

The Immortal Legacy of General Zorawar Singh: The Man Who Redrew the Himalayas

As snow continues to crown the towering peaks of Ladakh and Baltistan, and rivers trace ancient paths through Himalayan valleys, the story of one man flows eternally through the region’s veins—General Zorawar Singh, the bold Dogra warrior whose legacy is still felt today. His military genius, fierce ambition, and strategic clarity turned the modest Dogra state of Jammu into a mighty Himalayan domain. “In the span of eight years (1834–1841), he expanded the Dogra state of Jammu from a small hill principality into a sprawling Himalayan domain.” This transformation was not a tale of mere conquest, but of vision, blood, and legacy.

The conquest of Ladakh and Baltistan wasn’t just about territory—it was a prelude to a grander political evolution. “His conquests of Ladakh and Baltistan paved the way for the formation of the princely state of Jammu & Kashmir under Gulab Singh in 1846.” Following the First Anglo-Sikh War, even the British had to acknowledge the reality that Zorawar had carved out with his sword. “The British recognized Gulab Singh as Maharaja of an independent Jammu & Kashmir – which included Jammu, Kashmir Valley, Ladakh, Gilgit-Baltistan, and Zorawar’s other acquisitions.” It was a state built not just by diplomacy, but by the tireless campaigns and victories Zorawar Singh had fought with fire and steel.

One of Zorawar’s most extraordinary feats was his trans-Himalayan campaign into Tibet—an effort no other Indian general before or after him had accomplished. “Zorawar’s daring trans-Himalayan thrust also marked the first and only instance of an Indian kingdom extending armed influence into Tibet, earning him a unique place in history.” Though the gains in Tibet were temporary, they represented a daring military reach rarely witnessed in the subcontinent. “Although his Tibetan gains were short-lived, they demonstrated a strategic vision that reached beyond the subcontinent.”

|

Because of his stunning military achievements, historians often place Zorawar Singh alongside world-renowned conquerors. “For his high-altitude feats, Indian historians have dubbed him the ‘Napoleon of India’ or ‘Napoleon of the East,’ noting that he led campaigns in some of the world’s harshest terrains that invite comparison with Napoleon’s winter march on Russia.” However, the comparison only scratches the surface. Unlike Napoleon, Zorawar worked with far fewer men and resources. His campaigns were fueled by unbreakable morale, deep local understanding, and meticulous preparation. “Unlike Napoleon, Zorawar operated with relatively tiny forces and resources.”

In the biting Himalayan cold, where temperatures dropped to -40°C and the air thinned with altitude, Zorawar did the unthinkable: “His ability to train and motivate hill soldiers to fight effectively in -40°C blizzards and oxygen-thin elevations is frequently cited in military studies of mountain warfare.” His genius wasn’t only in battle, but in logistics too. “Modern analysts credit Zorawar’s campaign logistics – like pre-building supply depots and acclimatization of troops – as laying early foundations for high-altitude warfare tactics.” His legacy still shapes modern Indian military strategy. In April 2025, “Army Chief Gen. Upendra Dwivedi highlighted how Zorawar’s Himalayan campaigns ‘laid the foundation for principles later adopted in mountain warfare’ by India’s forces.”

Beyond the battlefield, Zorawar Singh lives on in the hearts of the people—especially in Jammu and Ladakh, where he is celebrated not just as a general, but as a symbol of Dogra pride. “In his home region, Zorawar Singh is venerated as a folk hero and symbol of Dogra valor.” The military lineage he helped establish continues to honor him. “The Jammu & Kashmir Rifles regiment (descendant of the Dogra forces) celebrates 15 April as ‘Zorawar Day’ each year, honoring his birth and battlefield successes.” And in the land he fought to bring under control, a piece of his soul remains. At Leh in Ladakh, a fort bearing his name still stands tall. “The historic Zorawar Fort (built by the general in 1836 to secure his Ladakhi conquest) still stands – now serving as a museum showcasing his weapons, portraits and war trophies.”

Inside the walls of this fort, stories come alive. “A statue of Zorawar Singh on horseback adorns the fort, and visitors learn how ‘from 1834 to 1841, General Zorawar Singh visited Ladakh, reinforcing the region’s boundaries and securing it for the Dogra dynasty’.” These aren’t just facts—they are memories etched in stone, soil, and snow.

Even after nearly two centuries, the borders Zorawar fought to defend and expand remain largely unchanged. “Nearly two centuries later, the boundaries General Zorawar fought to establish are largely intact – a testament to his lasting impact on South Asian geopolitics.” His military efforts ensured that Ladakh and Baltistan would stay connected with India—first under Dogra rule, and later as part of the Indian republic. “His conquests of Ladakh and Baltistan ensured these regions would be linked with India (via Dogra and later Indian rule) rather than Tibet or Central Asia.”

In a time when local rulers fought for patches of land, Zorawar dreamed of a united region, and then he made that dream a reality. “By ending the local internecine warfare and integrating these areas, Zorawar Singh helped define the modern frontiers of India’s Ladakh and Jammu-Kashmir.” Though he “fell on a foreign battlefield”, he left behind not just territory, but a blueprint for unity and strength. “His legacy endured: the 1842 treaty he effectively precipitated affirmed Ladakh as part of the Dogra (and later Indian) realm.”

And so, history records him not just as a general, but as a legend. “General Zorawar Singh’s extraordinary exploits across the Himalayas thus secured his place in history as one of 19th-century India’s greatest military commanders, whose strategic vision and fearless leadership left an indelible mark on the map of the subcontinent.”

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- Bhagat Irwin Gandhi - Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh (Some Hidden Facts)

- "Yogi seemed to be doing everything wrong, yet everything came out right": Story of an Unknown Hindu Yogi from the annals of freedom fights, who with a muscular build, sitting on a leopard skin killed a British Captain in front of the British Army in 1857

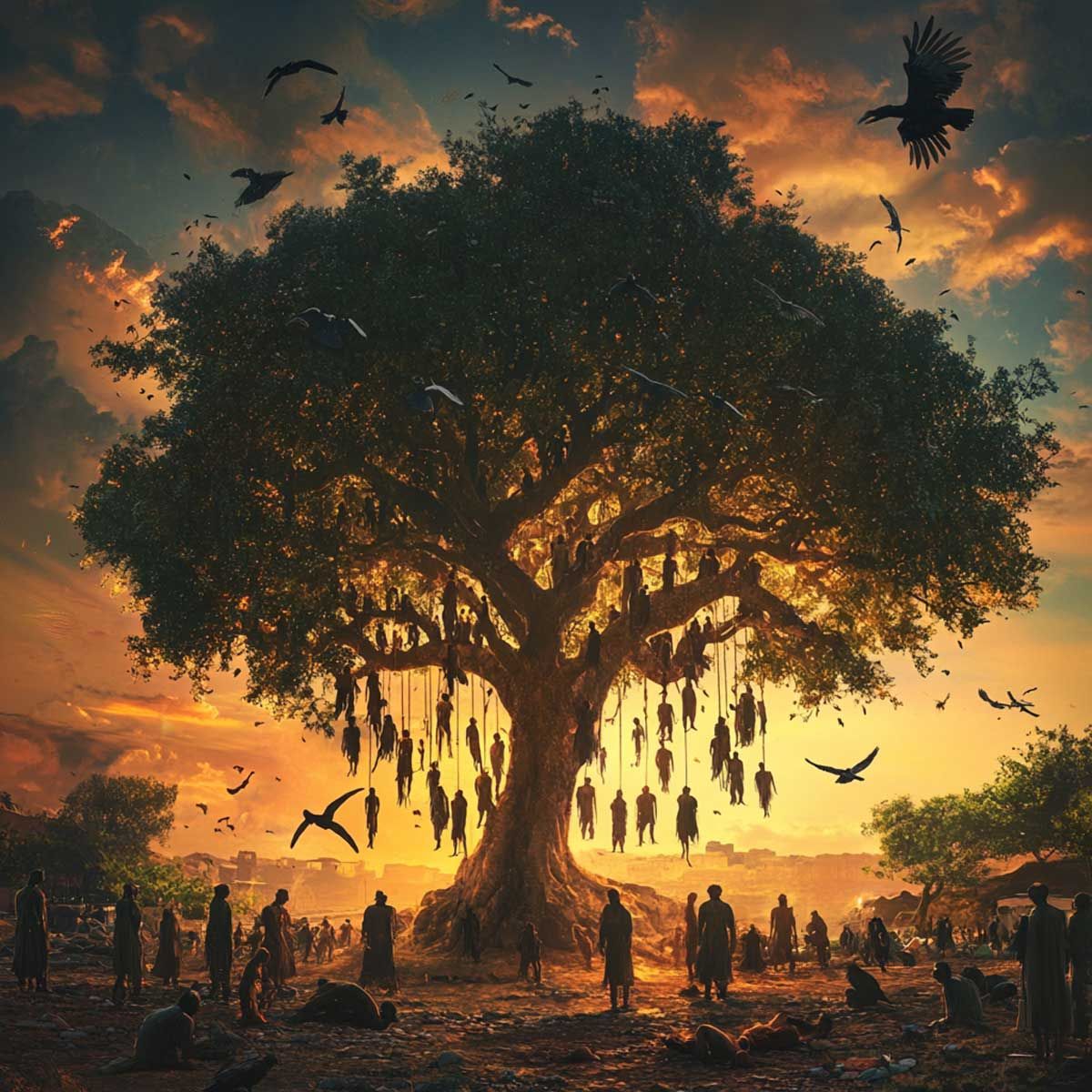

- "बावनी इमली": In 1858, at Bawani Imli in Fatehpur, 52 revolutionaries led by Jodha Singh Ataiya were brutally hanged from a tamarind tree by the British, a forgotten chapter of India's freedom struggle buried under decades of silence and neglect

- Martyrs’ march into the history - Rajguru: The Invincible Revolutionary

- Birth of our National Anthem: Original recording of 'Jana Gana Mana' performed by the Radio Symphony Orchestra of Hamburg, Germany, 1942 in the presence of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose

- Debunking the myth of "De Di humein Aazadi Bina Khadag Bina Dhal": Bharat’s founding story bestows upon it an extravagant national philosophy and long-lasting costs

- A revolutionist freedom fighter who the British Raj framed for murder

- The Eki Movement of hero Motilal Tejawat whose last wish is still waiting to be fulfilled - 100 years of Palchitaria massacre in Gujarat and its cover-up by the British govt

- "Tied to the cannon and blown to pieces couldn't deter his loyalty to Ettayapuram King and his devotion to the motherland stood sturdy and unshaken": Veeran Azhagumuthu Kone, Tamil Warrior who rebelled against Britishers 100 years before 1857 war

- "Courage makes a man more than himself; for he is then himself plus his valor": Surya Sen - hero behind Chittagong armory raid & attack on Europeans only club that shook British like never before, brutally tortured and executed by British on Jan 12, 1934

- Saraswathi Rajamani, at 16, became the youngest and first female spy for INA, boldly recruited by Netaji in 1942, courageously spent two years spying on the British in Myanmar during WWII, a pivotal yet overlooked heroine in India's struggle for freedom

- A Great man Beyond Criticism - Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh (Some Hidden Facts)

- Rani Chennamma of Keladi who fought bravely against Mughals and gave shelter to Shivaji’s son Rajaram, killed more than half of the forces of Aurangzeb's son Azamath Ara

- In a historical move ahead of Republic Day on January 26th, the Amar Jawan Jyoti flame at the India Gate would be merged with the flame at the National War Memorial on Friday

- Meet The Dark Knight Of Kargil, Manoj Kumar Pandey, Who Made Rambo Seem Like A Joke