More Coverage

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Join Satyaagrah Social Media

"The Forgotten Voice": As Dyer fired 1650 rounds into a trapped crowd & O'Dwyer silenced the press, thousands died at Jallianwala Bagh—only one man, Chettur Sankaran Nair rose alone, took on the Empire and forced the world to confront its colonial cruelty

The date was April 13, 1919, a day that marked the Punjabi New Year, known as Baisakhi, a time meant for celebration and joy. Yet, in the city of Amritsar, hundreds of Indians gathered at a place called Jallianwala Bagh—not just to ring in the festivities, but to raise their voices against a harsh new law imposed by the British rulers. This law, called the Rowlatt Act, had stirred anger across the nation, and nowhere was the unrest more palpable than in Punjab.

|

Among those who stood tall against this injustice was Chettur Sankaran Nair, a brilliant lawyer and a fierce nationalist whose courage deserves to be remembered. This is the story of a man who refused to stay silent while his people suffered.

The Rowlatt Act was a cruel piece of legislation that the British government forced upon India. It gave them the power to control where any Indian could go, locking them into certain areas far from their homes or jobs, with no chance to defend themselves in court. The police could swoop in, arrest anyone they didn’t like the look of, slap fines on them without reason, or rummage through their homes—all without a warrant. Naturally, this sparked fury among Indians. Nationwide strikes broke out as people refused to accept such tyranny. In Punjab, the situation was even grimmer. Nearly 400,000 Punjabis had been dragged into the British army to fight in World War I, their wheat snatched away to feed British soldiers, leaving families hungry at home. To make matters worse, Sir Michael O’Dwyer, the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, stood up and gave cold, heartless speeches defending the Rowlatt Act as if it were perfectly reasonable. The protests grew so fierce that O’Dwyer called in Brigadier General Reginald Dyer, a military man known for his quick temper and brutal ways, to crush the unrest in Amritsar.

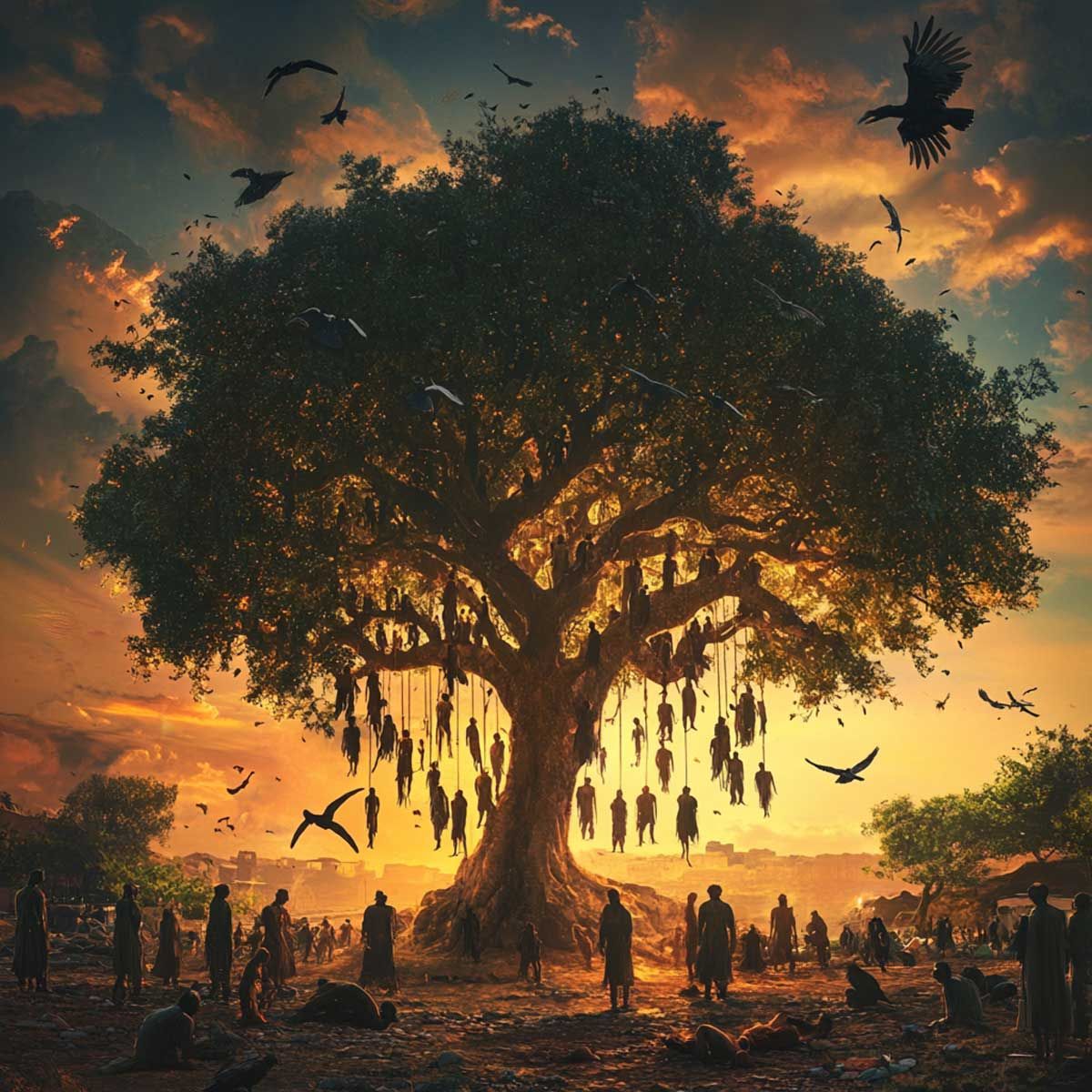

That fateful day, April 13, 1919, saw a horrific tragedy unfold at Jallianwala Bagh. A huge crowd of peaceful, unarmed Indians had gathered in this park, tucked away in a crowded part of Amritsar. Despite martial law clamping down on the city, nearly 25,000 people—Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims—filled the Bagh by the afternoon. Among them were women carrying babies, children running about, and elderly folks leaning on sticks. Some were there to protest the Rowlatt Act and the British oppression it stood for, especially bitter after India’s massive sacrifices in the war. Others had simply come to enjoy Baisakhi, a spring festival that brought families together. There was no hint of violence in their hearts—just a shared hope for freedom and a better tomorrow. But Brigadier General Dyer saw them differently. To him, they were all troublemakers, terrorists even, and he decided the army, not just the police, was needed to deal with them.

By 4:30 in the afternoon, Dyer marched in with ninety armed soldiers. He positioned them at the only entrance to Jallianwala Bagh, a narrow passage that trapped everyone inside. Without a single word of warning, the soldiers opened fire. For ten long minutes, bullets rained down on the crowd as the gates stayed blocked. They didn’t stop until every one of their 1,650 rounds was spent. When the smoke cleared, the ground was littered with bodies—380 people dead, 1,200 wounded. Women, children, and the elderly were among the fallen, their lives snuffed out in an act of unimaginable cruelty.

The scene that followed was pure terror. People dropped to the ground, hoping to dodge the bullets whizzing overhead. Some scrambled to climb the Bagh’s walls, only to be shot down as they tried. Others, desperate to escape, threw themselves into a well inside the park. Those who jumped in first were crushed to death under the weight of more bodies piling on top. A survivor, Moulvi Gholam Jilani, later shared his haunting memory: “I ran towards a wall and fell on a mass of dead and wounded persons. Many others fell on me… There was a heap of dead and wounded over me, under and all around me. I thought I was going to die.”

|

Meanwhile, Dyer sent a report to the British government, coolly defending his actions: “I realized that my force was small and to hesitate might induce attack. I immediately opened fire and dispersed the mob. I estimate that between 200 and 300 of the crowd were killed.”

Later, he showed no shred of regret, writing: “I think it quite possible that I could have dispersed them perhaps even without firing. But I didn’t do so because they would all come back and laugh at me and I considered I would be making myself a fool.” His arrogance and lack of remorse only deepened the wound inflicted on the Indian people.

Into this dark chapter stepped Chettur Sankaran Nair, a man of principle and a legal giant who wouldn’t let such an atrocity pass quietly. While the British tried to justify their actions, Nair became one of the loudest voices calling out their wrongs. He saw through the excuses of men like Dyer and O’Dwyer, who hid behind their power while innocent blood stained the ground. Nair’s fight wasn’t just for justice—it was for the soul of a nation tired of being trampled under British boots. His story, often overlooked, is a beacon of resistance against a colonial regime that cared little for the lives it ruled.

After the bloodbath at Jallianwala Bagh, Brigadier General Dyer didn’t face any real consequences—at least not right away. Instead, he had the full support of his superior, Michael O’Dwyer, the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, a man who ruled with an iron fist and a heart of stone. Together, these two British officials worked fast to bury the truth. They slapped martial law on Punjab and muzzled the press, making sure no one could speak freely about what had happened. The British administration didn’t want the world to know the scale of their brutality, so they twisted the story into something that suited their image. Meanwhile, the Indian people faced even more humiliation.

In the days that followed, the British forced Indians to crawl on their hands and knees through the streets and salute every Englishman they passed, treating them worse than animals. Local newspapers, which could have shouted the truth from the rooftops, were gagged—some were shut down completely. English journalists who dared to show sympathy for the Indian cause were packed off and sent back home. Even the 'Report on the Native Papers,' a regular update sent to London about what was happening in India, stayed eerily silent about the massacre. Instead, the British spun it as a necessary show of strength, a way to keep India in line and stop another rebellion like the one in 1857. For this, O’Dwyer and Dyer were praised as heroes by their own kind—men who had supposedly saved the empire.

But the truth couldn’t stay hidden forever. One brave British journalist, Benjamin Horniman, refused to bow to the censorship. He dug deep, uncovered the grim details, and shared them with the world, shining a light on the horror that the British wanted to keep in the shadows. His courage cracked open the wall of silence, and it set the stage for someone else to step up—a man from Kerala who would risk everything to fight for justice.

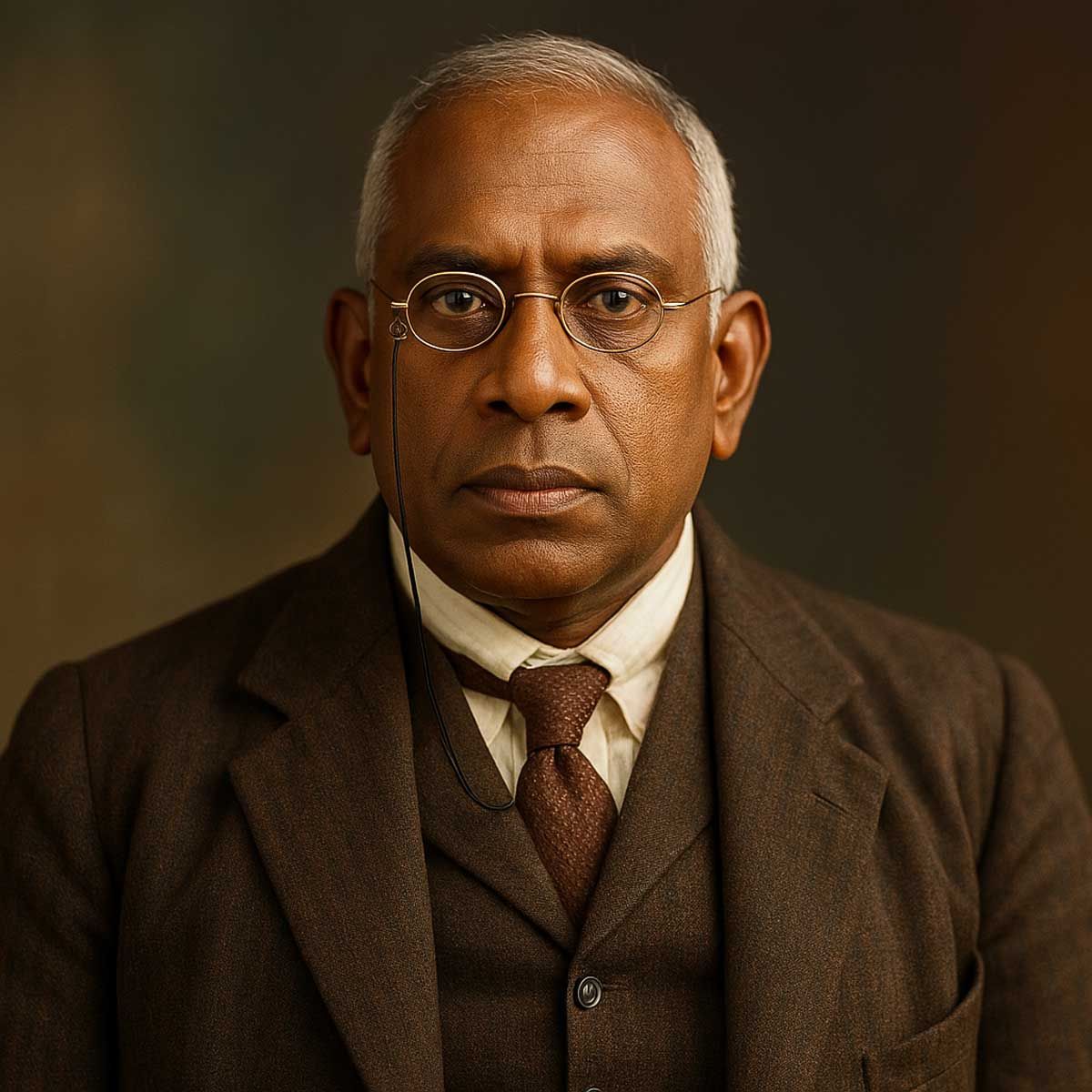

That man was Chettur Sankaran Nair, a legal expert and a member of the Viceroy’s Council, who couldn’t stomach what he’d heard. The Council, led by Lord Chelmsford, the British Viceroy, had just five members at the time, and Nair was the only Indian among them. When the news of Jallianwala Bagh finally trickled through the layers of censorship to reach him, he was shaken to his core. The thought of innocent men, women, and children gunned down in cold blood made him want to walk away from his prestigious post right then and there.

|

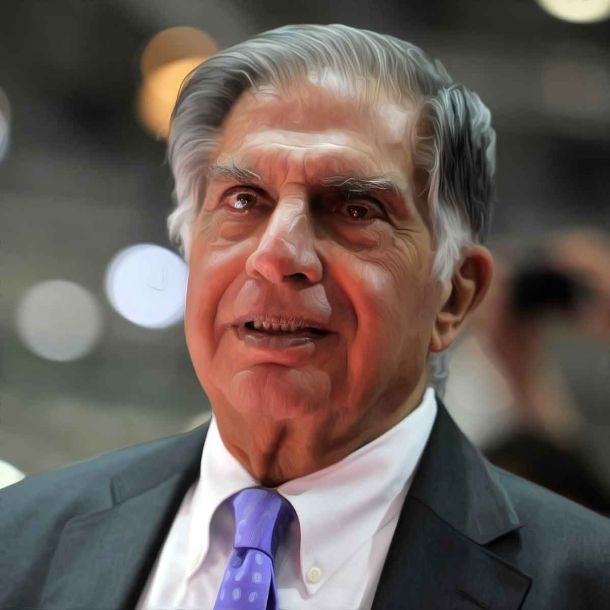

Who was Chettur Sankaran Nair?

To understand why Nair’s reaction mattered so much, you have to know who he was—a man of rare brilliance and unshakable principles. Born in the Palghat district of what’s now Kerala, he moved to Madras (today’s Chennai) to chase his dream of studying law. He didn’t just succeed—he soared. Nair climbed the ranks to become a renowned lawyer, then served as advocate-general, and by 1908, he was a judge at the Madras High Court. He wasn’t just a man in a courtroom, though—he helped start the Madras Law Journal, the oldest legal journal in India, still around today. Nair wasn’t afraid to push for change either. He spoke out for things that mattered: equal rights for women, an end to caste discrimination, stopping child marriages, and free education for kids. Even the British couldn’t ignore his sharp mind and honest character, so they knighted him in 1912, making him Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair.

By 1915, he’d risen even higher, earning a spot on the Viceroy’s Council. There, he wasn’t shy about speaking his mind, even when it clashed with British views. Often, his arguments were so solid that the British had to admit he was right. Nair wasn’t just a reformer—he was a proud nationalist too. Back in 1890, he’d joined the Legislative Council of Madras, and in 1897, he led the Indian National Congress conference. Indians admired his fire, and even some British officials respected his grit. He was a bridge between two worlds, trusted by both sides.

So when Nair heard about Jallianwala Bagh, it hit him hard. Holding the highest post an Indian could dream of under British rule, he wanted to quit on the spot. Leaders like Motilal Nehru begged him to stay, telling him he could do more good from the inside. Nair tried—he held on for three months, hoping Lord Chelmsford’s government would own up to the massacre. But to his dismay, they wouldn’t even admit they’d done anything wrong. By July 1919, he’d had enough. Furious and fed up, he resigned in protest, walking away from a job most could only dream of.

The Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, didn’t care much for Indian opinions, and even someone as respected as Nair wasn’t spared. In a final meeting, Chelmsford asked Nair if he could suggest a replacement. Nair, calm but cutting, said “Yes” and pointed to the uniformed doorkeeper standing nearby. The Viceroy’s face turned red with anger as Nair went on: “Why not? he is tall and handsome, wears his livery well and will say yes to whatever you say. He will make an excellent member of the council.” It was a stinging jab at how the British wanted yes-men, not thinkers. Nair didn’t care about the fallout—he’d just thrown away a golden career, one that could’ve kept him comfortable and powerful. But to him, staying silent would’ve been worse.

Was he crazy to give it all up? Some might’ve thought so. He was stepping into the unknown, risking obscurity. Yet, as his son-in-law and biographer KPS Menon later wrote, “his star was never brighter.” Nair didn’t see it as the end—ironically, it was the start of something bigger. And here’s the twist: his bold resignation wasn’t for nothing. It sent ripples through the British system, forcing people to pay attention. He might’ve walked away from the Council, but he didn’t walk away from the fight for Jallianwala Bagh’s victims. His stand shook things up more than anyone expected.

When Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair walked away from the Viceroy’s Council in July 1919, he didn’t just fade into the background. His bold resignation sent shockwaves through the British system, and the effects were felt almost immediately. The tight grip of censorship loosened—the ban on the press was lifted, letting newspapers breathe again. Martial law, which had choked Punjab with fear, was gone within two weeks. The Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, had no choice but to act. He set up the Hunter Committee to dig into the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and the wave of violence that followed in Punjab. Nair’s stand had forced their hand, and soon, he was on his way to London, invited to lay out the ugly facts before the British parliament. They even offered him a spot on the Council of the Secretary of State for India, a sign of how much his voice mattered.

|

In London, Nair didn’t hold back. He brought Dyer’s own words into the spotlight, showing how the general had admitted to planning the shooting to leave a “moral impact” on India. The British press couldn’t ignore it—the story exploded, stirring up outrage. Even the Viceroy had to admit that Dyer’s actions, from the massacre to the humiliating “crawling” orders, were downright inhumane. Dyer was shipped back from India, his dreams of a fancy title snatched away. He and O’Dwyer had bragged that they’d stopped a rebellion in its tracks, but the Hunter Committee saw through the lie. The report stated clearly: “there was no rebellion that required to be crushed.” Even Winston Churchill, a man who loved the British Empire with every fiber of his being, couldn’t defend them. He called it a complete mess, a stain on their rule.

The Hunter Committee didn’t mince words either. It slammed the Bagh massacre and the snap decision by O’Dwyer and Dyer to fire without warning, labeling it a “grave error.” The British parliament, Churchill, and the press piled on, demanding harsh punishment for the pair. But here’s where the British showed their true colors—despite all the evidence, Dyer escaped real consequences. His bosses had backed him, and he still had fans among powerful British politicians. Plus, his health was failing, so he slipped away by resigning. O’Dwyer’s name took a hit, or so it seemed at the time, but the story wasn’t over yet.

Back in Madras, Nair stepped off the boat to a hero’s welcome. Crowds cheered, grateful for a man who’d stood up to the British bullies. But Nair wasn’t like everyone else in the freedom fight. He didn’t see eye to eye with Mahatma Gandhi, who was pushing civil disobedience, non-cooperation, and non-violence as the road to independence. Nair worried those paths could spark riots and bloodshed, hurting innocent people caught in the chaos. For him, the fight had to stay within the law, using the constitution to win reforms step by step. He wasn’t afraid to say it either. In 1922, he poured his thoughts into a book called Gandhi and Anarchy, laying out his beliefs loud and clear. Not many nationalists cheered him on, but Nair didn’t care about winning a popularity contest—he was after the truth.

In that book, he carved out a whole chapter to call out the horrors in Punjab. He pointed the finger straight at O’Dwyer, saying the atrocities happened with the man’s “full knowledge.” Nair didn’t stop there—he tore into O’Dwyer’s abuse of power, painting a picture of a tyrant who’d let Punjab bleed. O’Dwyer, though, saw a chance to claw back some dignity. He called Nair’s words libel, a smear on his name, and demanded the book be pulled, an apology written, and a fine paid. When Nair refused, O’Dwyer sued him in 1923, claiming “Chettur’s book had tarnished his reputation.” But let’s be real—after the Hunter Committee’s report, O’Dwyer didn’t have much of a reputation left to save. This was just a desperate grab to look like the victim. The catch? The case landed in King’s Court in London, where Nair couldn’t count on a fair shake from the jury.

The trial stretched over five weeks—the longest ever in that court’s history. With two heavyweights like Nair and O’Dwyer slugging it out, the Empire and Punjab’s people watched every move. Some Brits still clung to the idea that Dyer’s brutality had saved their precious empire, while others, in both India and Britain, ached for the victims—thanks to Nair’s resignation waking them up. Both sides hauled in witnesses from India and England. O’Dwyer leaned on fancy landowners from the upper castes, while Nair brought in real people—folks from all walks of life who’d felt the pain firsthand. The courtroom buzzed every day, packed with onlookers, including big names like the Maharaja of Bikaner.

Nair and his lawyer argued that every word in Gandhi and Anarchy was true, written for the public good. Fifteen witnesses backed him up, swearing the massacre came out of nowhere—“unannounced”—and that even those running for their lives were shot down without mercy. They told gut-wrenching stories: stripped naked, beaten with sticks, thorns shoved between their legs, handcuffed and forced to sit on spikes under the blazing sun, or bent double while grabbing their ears through their legs. Nair didn’t just talk about it—he showed it, acting out the torture in court. The room gasped as one, the image searing into their minds. O’Dwyer’s team scrambled to paint him as a decent man tangled up in Dyer’s bad calls, but the evidence was a mountain they couldn’t climb.

|

Still, the deck was stacked. The trial was in England, O’Dwyer’s turf, with a judge who’d hinted at favoring him from day one and an all-British jury. After fierce arguments, the jury couldn’t agree, so both sides settled for a majority vote. Eleven out of twelve jurors sided with O’Dwyer, with just one—Harold Laski, a sharp-minded political economist—standing by Nair. To Nair, that lone voice was a win in itself. Since the jury wasn’t unanimous, he could’ve pushed for a new trial, but the cost was steep. He was ordered to pay O’Dwyer 500 GBP—a fortune for an Indian back then—plus court fees. It was a heavy blow, but Nair didn’t blink. He paid up rather than bend to a man like O’Dwyer, a petty tyrant hiding behind a crumbling facade.

After the long trial in London, Michael O’Dwyer tried one last trick to save face. He told Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair he’d drop the demand for the 500 GBP fine and court costs if Nair would just apologize for what he’d written in Gandhi and Anarchy. But Nair wasn’t the kind of man to back down. His refusal rang out in the courtroom like a thunderclap, clear and unshakable. He didn’t just pay the fine—he shut the door on any chance of appeal too. When someone asked why he wouldn’t fight the verdict again, he said, “If there were another trial, who was to know if 12 other English shopkeepers would not reach the same conclusion?” People worried about what this meant for his good name, pressing him with, “But what about your reputation?” Nair’s answer was pure steel: “If all the judges of the King’s Bench together were to hold me guilty, my reputation will still not suffer.”

The British press circled him too, asking if the loss had dented his honor. Nair stood tall and told them that even if every judge in the King’s Court lined up to call him guilty, it wouldn’t touch his reputation one bit. He’d lost on paper, sure, but in the bigger picture, he’d won something far greater. Those five weeks in court hadn’t been for nothing—day after day, the world heard about the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, a story the British had tried so hard to bury. The spotlight forced their hand: press restrictions in India were scrapped, martial law in Punjab was history, and Britain faced a new kind of pressure. People everywhere started demanding better treatment for Indians and a say in their own governance. Nair’s fight had cracked open a door that wouldn’t close again.

Sir Nair had taken on this battle alone, facing down a vicious enemy with nothing but his courage and his belief in what was right. The courtroom might’ve ruled against him, but in the hearts of millions of Indians, he was a champion—a hero who’d stood up when they couldn’t. Down at Jallianwala Bagh today, there’s a plaque at the museum entrance honoring him, a quiet tribute to a man who refused to let the massacre fade into silence. He’s an unsung giant of India’s freedom story, a name that should echo louder than it does.

Even though the law didn’t side with him, the O’Dwyer vs. Nair case did what Nair had set out to do: it shouted the truth about Jallianwala Bagh to the world, making sure such a nightmare wouldn’t happen again. The British press split down the middle—those who’d cheered Dyer backed the verdict, while others, who felt for the Indian cause, blasted the judge’s bias as a shameful mark on British justice. Indian newspapers didn’t hold back either, tearing into the judge and the whole British system. They were gutted about Nair’s loss, but their words lifted him higher, calling him a patriot and a leader worth admiring. Even Winston Churchill, speaking in parliament, couldn’t dodge the weight of it all. He called the massacre “an episode which appears to me to be without precedent or parallel in the modern history of the British Empire… It is an extraordinary event, a monstrous event, an event which stands in singular and sinister isolation.” The words hung heavy, a rare admission from a man who rarely bent.

Back home in Madras, Nair didn’t fade away. Both Indian nationalists and British officials kept knocking on his door, seeking his advice. He’d earned that kind of respect, the kind that doesn’t vanish with a lost case. He lived out his days there until he passed away peacefully in 1934. Time might’ve dimmed his name for some, but there are still pieces of his legacy standing strong. His family set up the Chettur Sankaran Nair Foundation to keep his spirit alive, working for social and cultural good. And then there’s something you can see with your own eyes—a 30-foot lamp, a deepastambham with 300 wicks, glowing at the entrance of the Guruvayoor temple in Kerala. Nair donated it himself, a light that still burns bright, just like the man he was.

|

Sardar Udham Singh

Now, what about the two men who’d brought so much pain to Jallianwala Bagh—Dyer and O’Dwyer? Their masks of glory didn’t last long. Once the truth spilled out, both were stripped of their posts, though at first, some still patted them on the back. Dyer had a fleeting moment in the sun when a group of racist women handed him a sword of honor, dubbing him the “saviour of Punjab.” But the tide turned fast. People saw through the lie, and he retreated into a lonely life. A series of strokes left him broken, and he died a sick, forgotten man in 1927.

O’Dwyer hung on longer, trying to rewrite his story. In 1925, he published a book claiming his actions were just tough anti-terrorism moves, nothing more. He kept scribbling columns in the Times newspaper, trashing Gandhi and singing praises for British rule. But fate wasn’t done with him. A young Indian named Udham Singh, a survivor of Jallianwala Bagh, had been carrying a wound—and a promise—for 20 years. Shot and scarred in that massacre, he spent two decades plotting, waiting for the right moment. In 1940, he made his move. He traveled to London, tracked O’Dwyer to a public meeting, and shot him dead on the spot.

Udham Singh didn’t run. He stood there, calm as stone, and said, “It was my duty (to kill O’Dwyer). What greater honour could be bestowed on me than death for the sake of my motherland?” His words weren’t just defiance—they were a cry from every soul lost at the Bagh. He’d waited, planned, and struck, closing a chapter Dyer’s bullets had opened. For Nair, it was the courts and the pen; for Udham, it was a gun. Two men, two paths, but both fighting for the same justice.

|

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- “Sometimes you have to pick the gun up to put the Gun down”: Bhagwati Charan Vohra and Bhagat Singh threw ‘Philosophy of Bomb’ in response to "Cult of Bomb" by Gandhi who launched a crusade against revolutionaries that cost him his career

- Kartar Singh Sarabha - The Freedom fighter who was Hanged at the age of 19 and inspired Bhagat Singh

- Meet The Dark Knight Of Kargil, Manoj Kumar Pandey, Who Made Rambo Seem Like A Joke

- Cross Agent and the hidden truth of massacre of Jallianwala Bagh - Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh (Some Hidden Facts)

- Godse's speech and analysis of fanaticism of Gandhi: Hindus should never be angry against Muslims

- "Behold it is born. It is already sanctioned by the blood of martyred Indian youths": Madam Bhikhaiji Cama, the Brave lady to first hoist India’s flag on foreign Soil - Formative Years

- Jhalkaribai: The Indian Rebellion Of 1857 Who Took on British Forces Disguised as Laxmibai

- "समुद्रातळ शिवाजी": Behold mighty Kanhoji Angre, born 1669 in Harne, a fearless Maratha Navy hero ruling the Arabian Sea from Surat to Konkan with 80 ships, smashing British, Dutch, and Portuguese foes for 40 years, fortifying Vijayadurg and Alibag

- Martyrs’ march into the history - Rajguru: The Invincible Revolutionary

- "It is the cause, not the death, that makes the martyr": Durga Devi Vohra supported her husband to go and blow Britishers, helped Bhagat Singh and Rajguru with money and escape, opened fire on Governor Halley, and shot the Police Commissioner of Mumbai

- "Unsung today, but forever in our hearts": Before the 1857 Revolt, Veerapandiya Kattabomman fiercely defied British dominance in Tamil Nadu, his unyielding spirit and sacrifice remain a testament to India's unsung heroes who paved the way for independence

- Vinayak Damodar Savarkar – A Misunderstood Legacy

- "You can't serve the public good without the truth as a bottom line": Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi - activist journalist who used journalism to aspire political engagement & develop critical thinking among the masses, who lived- and died- for communal harmony

- "Remember that the greatest crime is to compromise with injustice and wrong": NSA Ajit Doval during the inaugural at Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Memorial event in New Delhi claimed that "India would not have been partitioned if Subhas Bose was alive"

- Birth of our National Anthem: Original recording of 'Jana Gana Mana' performed by the Radio Symphony Orchestra of Hamburg, Germany, 1942 in the presence of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose