More Coverage

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Join Satyaagrah Social Media

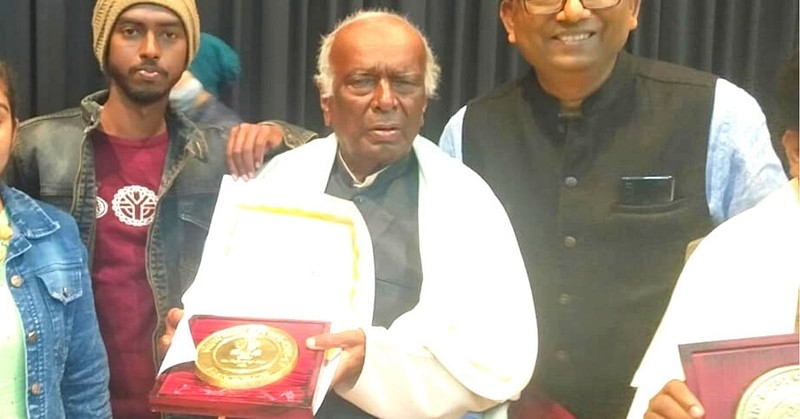

Taunted For His ‘Naach’, Ramchandra Manjhi - The last scion of Bhikhari Thakur’s tradition wins Padma Shri

Ramchandra Manjhi may have won the Padma Shri, India’s fourth-highest civilian award and Sangeet Natak Akademi, but his biggest achievement is something else.

A resident of Bihar’s Chapra district, he has been performing ‘Naach’, a musical theatre performance for the last 84 years. His ability to perform on stage with the same zeal and passion despite his weak eyesight and age-related ailments, occupies the number one spot in his list of accomplishments.

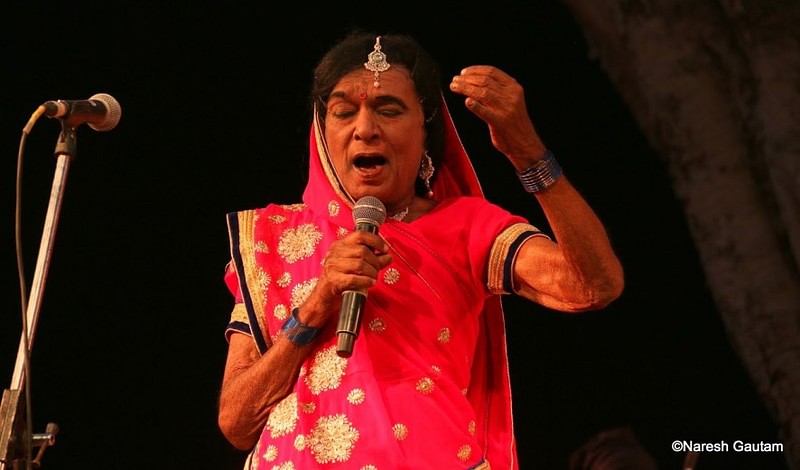

Just a month ago, the 97-year-old had donned a ghagra choli, did his own make-up and delivered an arresting performance in West Champaran on World Yoga Day. While performing he may have lost his balance and not achieved the near-perfect thumka but his eyes, voice and body language as a sautan (mistress) in Bidesiya, a popular play written by late Bhikari Thakur, received a standing ovation.

By the end of the day, he was a completely different person — a knowledgeable grandfather leading conversations on current political and social affairs with his neighbours in the village. The transition from a grandfather to a woman yearning for love while dealing with societal pressures comes as a shock to many and that for him is his biggest award.

Ramchandra Manjhi receiving Lifetime Achievement award |

Ramchandra joined the performing arts when he was barely 10. At the time, Naach had just started to flourish in the hinterlands of Bihar and money was good so his parents didn’t mind if their son was a cross-dresser. In fact, the by-products of theatrical performance—money and fame—made it honourable.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t how the world was going to perceive Naach. The visible caste barriers sprung up and dethroned the artform from its reputed position. However, Ramchandra kept at it for this was not just his livelihood but also a medium of change.

This is probably the reason why, even at this age, Ramchandra gets ecstatic every time he has to essay a woman.

“I have done Naach all my life. It is my identity. Performance is part of any artist’s routine just like brushing teeth. Naach has been there for me at every stage of my life, and my reasons to do it have evolved with each passing decade — starting from money, pleasure, joy, spreading awareness to now preserving this dying art form,” Ramchandra tells The Better India.

He is presently associated with the Bhikhari Thakur Repertory Training & Research Centre, a troupe run by Dr Jainendra Dost, a JNU scholar in Performing Arts.

“Ramchandra is one of the four living legends who can pass on his craft to the younger generations. He is not only performing for us but also spreading his wisdom and skills to others to keep Naach alive,” Dost says.

|

History of ‘Launda Naach’

Contrary to popular belief, Naach (meaning ‘dance’) is not a traditional folk dance of Bihar. It is the equivalent of Jaatra, Tamasha or Nautanki, where a troupe performs on ancient folklores and current social conditions to preserve their heritage while educating people in an entertaining fashion. In Naach, female characters are portrayed by the male who cross dress as women.

These men are known as ‘laundas’, meaning — young boys.

However, the story behind how ‘Launda Naach’ came to be associated as a vulgar art form lies in India’s deep-rooted caste system.

“In the Indian cultural context, tawaifs (courtesans) have held significant importance in palaces and mansions of the kings and lords of the Mughal era. It is believed that the period of Baiji Naach arrived after the tawaifs. Landlords and moneylenders were the main organisers of Baiji Naach during special occasions such as marriage ceremonies and festivals. While this catered to the higher strata of society, Naach performed by men was popular among the lower and middle-class in the villages. It is believed that the term launda (male performer) was used to differentiate it from baiji (female performer),” Dost writes in his 2017 paper on Naach, Launda Naach.

As most themes of Launda Naach revolve around oppression faced by the Dalits and people from lower castes, it was not well-received by the upper caste. For instance, in Lakhdev Ram’s play Ghurva Chamaar (1965), a Dalit man is allowed to enter a temple after he tells the priest he has gold coins to offer. However, he is brutally assaulted when the Queen realises a Dalit has stepped inside the temple.

Such storylines, Dost says, prompted the feudal system to degrade Naach. While it is true that the performances have a touch of erotica in them, it is only a strategy to keep the audience engaged throughout the show that goes on all night.

Coming to the structure of Naach, it is conducted on a wooden stage with live musicians playing the harmonium, naquara, dholak, tabla, jhal and sarangi. There is a small tent attached at the back that doubles up as a make-up room and storage.

“Naach begins around 8 pm with a prayer followed by songs in Bhojpuri, solo dance, group dance, a commentary on social or political satire. The play begins around midnight and goes on till 4-5 am. The reason behind keeping the shows so late is that in the past, villagers would travel for miles to catch the show but returning late in the night was not an option. Secondly, the audiences that predominantly comprise masons, wage labourers, domestic workers, farmers, etc, were available only late in the evening,” Dost says.

He adds, “Naach is performed only by invite on special occasions like birthdays, funerals, weddings and so on. The significance of Naach is such that some politicians like Lalu Prasad Yadav have used it to connect with the communities. People from all strata of society appreciate the art form as long as the themes don’t ruffle feathers.”

Among the many playwrights that honed Naach over the decades, Bhikhari Thakur (1887-1971) deserves a special mention. He not only popularised the artform beyond Bihar in West Bengal and Assam but also delved into subjects like dowry, child marriage, migration, caste discrimination, domestic abuse, addiction, which were otherwise brushed under the carpet.

Plays such as Bidesia, Beti Bechwa, Ganga-Snan, Gabarghichor and Kaliyug- Prem, and songs such as Ramlila-Gaan, Budhshala ke Beyan advocated for individual’s rights.

Ramchandra Manjhi during one of his stage performances. Image credit Naresh Gautam |

Countering Normative Masculinity

Ramchandra’s singing talent was recognised by a family friend when he was 10. Upon asking if he could sing in front of a small audience, he delivered a fine job. That earned him a place in a local troupe and his parents were on board. At least someone would bring in the money, they thought. He tells me that dressing up as a woman for Naach was considered respectful in his community back then.

“The more I performed, the more I loved it. I felt like a magician with all eyes on me. Seeing their mesmerised faces, I thought I had the power to make them feel different emotions. The highlight of my performances would be people falling in the well or from a tree. That was our yardstick to know it was a full house,” says Ramchandra.

Dressing up as a woman and revealing his feminine side was never a problem. On the contrary, it is an honour to highlight the atrocities to women. “In my career spanning eight-decades, several men have come up to me and assured me that they will respect their wives, sisters and daughters more. Some even shed tears while I am performing. This is the power of any art form, it can undo years of customs and perceptions.”

Ramchandra may not realise it but by donning the ghaghra and being comfortable in his skin, he has countered the normative masculinity for years.

Now 94 Manjhi has been on stage since he was 10 years old. Photo courtesy Naresh Gautam Bhikhari Thakur Repertory Training Research Centre |

But he warns of a flip side

“Either I am mocked for not being ‘a man’ or I am sexually harassed, sometimes even physically assaulted just because they see me as a woman. It tells a lot about our society. Men believe it is their prerogative to oppress the opposite gender. It is very common for men to poke bhalas (pointed weapons) on my stomach when I go near them to take the money.”

Over the years, Ramchandra has learnt to tackle such men. He even goes to the extent of sitting with them and explaining what they are doing is wrong. Likewise, opening up dialogues on child marriage and addiction is part of his after-performance. He claims people in his village have stopped selling their young daughters to older men.

For his most memorable performances, Ramchandra digs hard into his memory and narrates an incident that occurred in pre-Independence days.

“We were in Assam for a show to be staged in a theatre. Tickets were sold quickly and we had all the necessary permissions from the Britishers. The craze was such that people stopped watching movies for a few days to see us and this affected the revenue of theatre owners. They all ganged up on us and kicked us out of the city. On a more pleasant note, sharing a stage and wigs with yesteryear actresses like Helen, Suraya and Sadhana, is something I will never forget,” he says.

In his 80 years on stage, Manjhi says he has toured various cities of India, performed in government-sponsored cultural spaces to stages paid for by upper caste landlords, attracted cheers and jeers, but made sure his art stayed democratic.

“I was always clear that my first duty was to the village audience that can’t access or enjoy the more effete forms of entertainment. Our ticket prices have not gone up beyond a point, if a show is scheduled at a village and a richer man offers more money on the same day, I refuse. We travel hundreds of kilometres, going village to village, but we often choose to walk than make our poorer patrons pay for travel costs,” says the 94-year-old artiste.

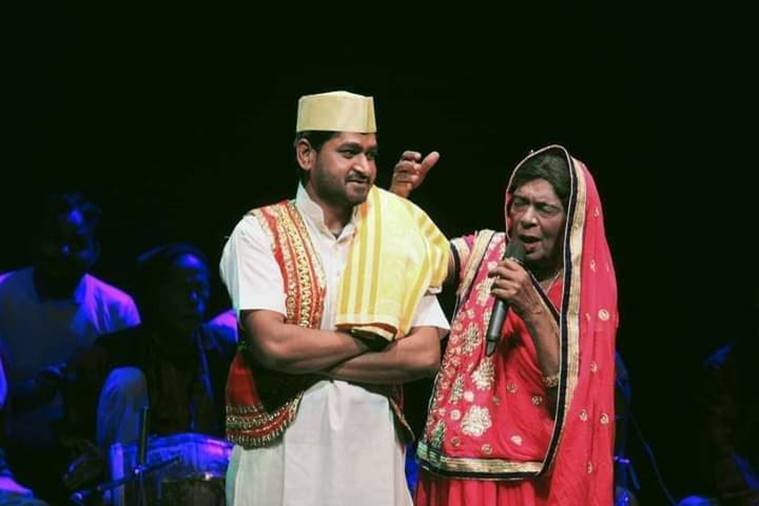

Dost left and Manjhi on stage. Photo courtesy Naresh Gautam/Bhikhari Thakur Repertory Training Research Centre |

Helping Manjhi with the conference call is Dr Jainendra Dost, a JNU scholar who now runs the Bhikhari Thakur Repertory Training & Research Centre in Chhapra. Dost says Manjhi’s life on stage has involved battling economic odds, caste discrimination, taunts for dressing up as a woman, but he has kept at it, powered by the need for public self-expression of a community historically denied that privilege.

“Thakur belonged to the low nai (barber) caste. He wrote about the subaltern among the subaltern –– the able-bodied lower caste man left to cities for work, leaving behind broken, vulnerable families, something very much happening in today’s Bihar too. He was the first to bring their stories to stage. That Bhojpuri never produced another Bhikhari Thakur shows the hold upper castes continue to have on art, and that’s one reason why Manjhi and his troupe, all elderly men now, hold on to the stage –– if they leave, who tells their stories?” Dost says.

Even today, says Dost, the way naach is consumed by upper and lower castes in villages is different –– the upper castes are watching hired artistes, the lower castes are watching their own people bring their stories alive. “When Thakur started writing, his audience could not afford the baijis (courtesans) the upper castes patronised. So men performed women’s parts too. But upper castes called it launda naach, a derogatory term that has stuck, forming a negative perception about the art form,” he adds. “Till a few years ago, when Ramchandra ji would perform at stages paid for by upper castes, men would poke their stomachs with bhalas (long, pointed weapon), currency notes stuck on the tip. They are often taunted with vulgar slurs over dressing up as women.”

Manjhi is more peaceable about it. “Well, I do wear saaris and make-up, so why should I mind if I am called effeminate? Over the years, we have learnt how to deal with these things –– we know when to diffuse a situation with a smile, or when to turn stern,” says the father of four sons.

The quest to keep his art accessible has meant Manjhi is still far from a rich man –– with his Padma Shri winnings, he hopes to build a toilet at his house. Does he think the award will get his art more recognition?

“The Padma Shri will hopefully mean more people outside Bihar hear of us, but we have never lacked recognition. Recognition is not 50-100 “sophisticated” people knowing your name, it is the love you get on stage,” Manjhi is firm. “I have learnt Kathak, I can sing several classical ragas. But that is not what my audience connects with. I intend to give my audience quality content they can enjoy. So-called refinement and respectability, at the cost of mass connect, is just stupid.”

With the money earned from Naach, Ramchandra purchased a house, married off his siblings, and later, all his children. He now lives with his granddaughter in his village.

Ramchandra has overcome gender and caste-based prejudices, financial crisis and several other odds to keep his tradition alive. He believes that art is the only avenue to be inspired from and inspire countless others.

References:

patnabeats.com - Satyam Kumar

thebetterindia.com - Edited by Yoshita Rao

indianexpress.com - Written by Yashee , Ashish Kumar Jha | Madhubani, New Delhi

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- Upset activist breaks into ‘Naagin dance’ on TV news: Roshni Ali lamenting about firecrackers and oxygen

- Set of 'Ashram3' series ransacked by Bajrang Dal Activists, Throw ink at producer Prakash Jha's face

- Veteran actor Dilip Kumar passes away at 98

- Sonam Kapoor steps in to support Woke ‘activists’ over NCERT controversy, dragged the RSS too

- Comparing Holi with terrorism and reducing Navratri to ‘mating dance’ — how the Indian media has turned Hinduphobic

- Knowing no boundary for hate, liberals descended on social media platforms to celebrate the death of legendary singer Lata Mangeshkar, calling her a ‘fascist’ and a ‘vile sanghi’

- Actor Siddharth was hailed as a reformer champion for women empowerment by SheThePeople, but he turned out to be anything but ‘feminist icon’

- Netflix CEO Reed Hastings expressed his ‘frustration’ over its poor performance in India after shares plummet by 21%, netizens were quick to show the mirror to the streaming platform and blamed its ‘woke bullsh*t’ content

- Srirangam temple’s Aandal Elephant walking in conversation with her caretaker Rajesh goes viral: Fact Check

- Bollywood 'Shocked', 'Angry' After Court Rejects Aryan Khan's Bail

- Gangubai Kathiawadi role played by Alia Bhatt of a madame sexually assaulted by the mafia is a new sensation and Filmfare promotes kids to recreate the same look: Indian parents need to be cautious

- Birsa Munda: The tribal folk hero who was God to his people by the age of 25

- The forgotten temple village of Bharat: Maluti

- ‘Will they give livelihood 100 million farmers’: Amul MD responds to PETA India for asking them to use ‘vegan milk’ after losing a case to Amul

- NCERT turns woke with sex-interested contributor Vikramaditya Sahai pushing gender jargon on children: How LGBT activists are calling legitimate criticism of a public figure ‘transphobia’