MORE COVERAGE

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

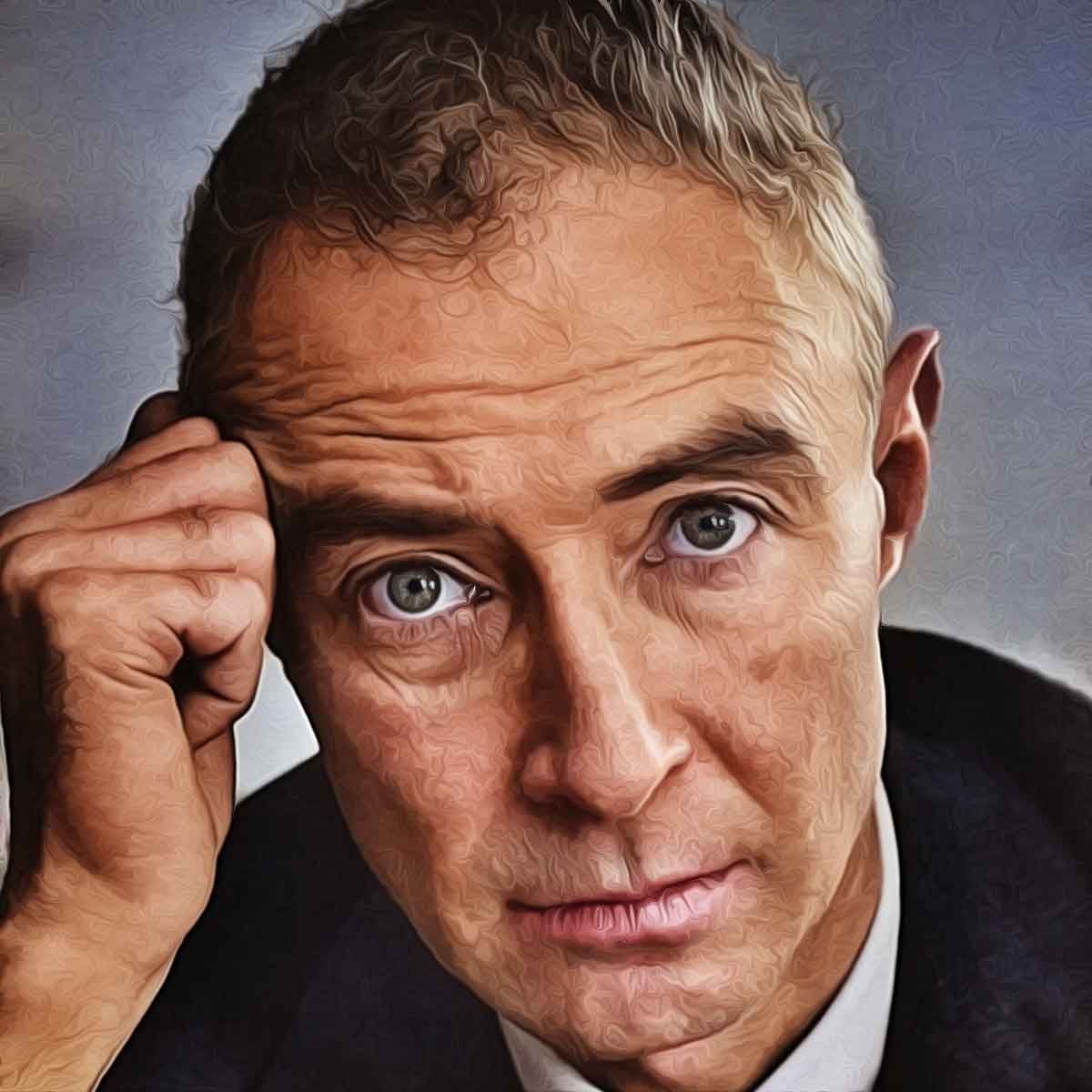

"You are what you believe in. You become that which you believe you can become": J Robert Oppenheimer, a theoretical Physicist recited a quote from Bhagavad Gita after witnessing first Nuclear explosion - "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds"

No matter how little we know of the Hindu religion, a line from one of its holy scriptures lives within us all: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” This is one facet of the legacy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, an American theoretical physicist who left an outsized mark on history. For his crucial role in the Manhattan Project that during World War II produced the first nuclear weapons, he’s now remembered as the”father of the atomic bomb.”

|

He secured that title on July 16, 1945, the day of the test in the New Mexican desert that proved these experimental weapons actually work — that is, they could wreak a kind of destruction previously only seen in visions of the end of the world.

As he witnessed the first detonation of a nuclear weapon on July 16, 1945, a piece of Hindu scripture ran through the mind of Robert Oppenheimer: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”. It is, perhaps, the most well-known line from the Bhagavad-Gita, but also the most misunderstood.

Oppenheimer died at the age of sixty-two in Princeton, New Jersey on February 18, 1967. As wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory, the birthplace of the Manhattan Project, he is rightly seen as the “father” of the atomic bomb. “We knew the world would not be the same,” he later recalled. “A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent.” Oppenheimer, watching the fireball of the Trinity nuclear test, turned to Hinduism. While he never became a Hindu in the devotional sense, Oppenheimer found it a useful philosophy to structure his life around. "He was obviously very attracted to this philosophy,” says Rev Dr Stephen Thompson, who holds a PhD in Sanskrit grammar and is currently reading a DPhil at Oxford University on other aspects of the language and Hindu faith. Oppenheimer’s interest in Hinduism was about more than a soundbite, it was a way of making sense of his actions.

|

“We knew the world would not be the same,” Oppenheimer remembered in 1965. “A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, ‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.'” The translation’s grammatical archaism made it even more powerful, resonating with lines in Tennyson (“I am become a name, for always roaming with a hungry heart”), Shakespeare (“I am come to know your pleasure”), and the Bible (“I am come a light into the world, that whosoever believeth on me should not abide in darkness”).

But what is death, as the Gita sees it? In an interview with Wired, Sanskrit scholar Stephen Thompson explains that, in the original, the word that Oppenheimer speaks as “death” refers to “literally the world-destroying time.” This means that “irrespective of what Arjuna does” — Arjuna being the aforementioned prince, the narrative’s protagonist — everything is in the hands of the divine.” Oppenheimer would have learned all this while teaching in the 1930s at Berkeley, where he learned Sanskrit and read the Gita in the original. This created in him, said his colleague Isidor Rabi, “a feeling of mystery of the universe that surrounded him like a fog.”

The necessity of the United States’ subsequent dropping of not one but two atomic bombs on Japan, examined in the 1965 documentary The Decision to Drop the Bomb, remains a matter of debate. Oppenheimer went on to oppose nuclear weapons, describing himself to an appalled President Harry Truman as having “blood on my hands.” But in developing them, could he have simply seen himself as a modern Prince Arjuna? “It has been argued by scholars,” writes the Economic Times‘ Mayank Chhaya, “that Oppenheimer’s approach to the atomic bomb was that of doing his duty as part of his dharma as prescribed in the Gita.” He knew, to quote another line from that scripture brought to mind by the nuclear explosion, that “if the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst into the sky that would be like the splendor of the Mighty One” — and perhaps also that splendor and wrath may be one.

|

Bhagavad-Gita is 700-verse Hindu scripture

The Bhagavad-Gita is 700-verse Hindu scripture, written in Sanskrit, that centres on a dialogue between a great warrior prince called Arjuna and his charioteer Lord Krishna, an incarnation of Vishnu. Facing an opposing army containing his friends and relatives, Arjuna is torn. But Krishna teaches him about a higher philosophy that will enable him to carry out his duties as a warrior irrespective of his personal concerns. This is known as the dharma, or holy duty. It is one of the four key lessons of the Bhagavad-Gita: desire or lust; wealth; the desire for righteousness or dharma; and the final state of total liberation, or moksha

Seeking his counsel, Arjuna asks Krishna to reveal his universal form. Krishna obliges, and in verse twelve of the Gita he manifests as a sublime, terrifying being of many mouths and eyes. It is this moment that entered Oppenheimer’s mind in July 1945. “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendour of the mighty one,” was Oppenheimer’s translation of that moment in the desert of New Mexico.

In Hinduism, which has a non-linear concept of time, the great god is not only involved in the creation, but also the dissolution. In verse thirty-two, Krishna speaks the line brought to global attention by Oppenheimer. "The quotation 'Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds', is literally the world-destroying time,” explains Thompson, adding that Oppenheimer’s Sanskrit teacher chose to translate “world-destroying time” as “death”, a common interpretation. Its meaning is simple: irrespective of what Arjuna does, everything is in the hands of the divine.

|

"Arjuna is a soldier, he has a duty to fight. Krishna not Arjuna will determine who lives and who dies and Arjuna should neither mourn nor rejoice over what fate has in store, but should be sublimely unattached to such results,” says Thompson. “And ultimately the most important thing is he should be devoted to Krishna. His faith will save Arjuna's soul." But Oppenheimer, seemingly, was never able to achieve this peace. "In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humour, no overstatements can quite extinguish," he said two years after the Trinity explosion, "the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.”

“He doesn't seem to believe that the soul is eternal, whereas Arjuna does,” says Thompson. “The fourth argument in the Gita is really that death is an illusion, that we're not born and we don't die. That's the philosophy really: that there's only one consciousness and that the whole of creation is a wonderful play.” Oppenheimer, it can be inferred, never believed that the people killed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki would not suffer. While he carried out his work dutifully, he could never accept that this could liberate him from the cycle of life and death. In stark contrast, Arjuna realises his error and decides to join the battle.

|

“Krishna is saying you have to simply do your duty as a warrior,” says Thompson. “If you were a priest you wouldn't have to do this, but you are a warrior and you have to perform it. In the larger scheme of things, presumably The Bomb represented the path of the battle against the forces of evil, which were epitomised by the forces of fascism.”

For Arjuna, it may have been comparatively easy to be indifferent to war because he believed the souls of his opponents would live on regardless. But Oppenheimer felt the consequences of the atomic bomb acutely. “He hadn't got that confidence that the destruction, ultimately, was an illusion,” says Thompson. Oppenheimer’s apparent inability to accept the idea of an immortal soul would always weigh heavy on his mind.

References:

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- Bhagwad Gita course for corporates is all set to launch at IIM Ahmedabad, will teach management and leadership

- A Different 9/11: How Vivekananda Won Americans’ Hearts and Minds

- "आंधी": Pawan Kalyan announces Varahi Declaration, calls for national & state boards to protect Sanatana Dharma, exposing Jagan's corrupt TTD leadership, misuse of temple funds, impurity in TTD laddus, and condemning biased legal treatment against Hindus

- PM Narendra Modi inaugurated the Statue of Equality of Sri Ramanujacharya and emphasized 'Progressiveness does not mean detaching from one’s roots and that there is no conflict between progressiveness and antiquity.'

- Temple city Madurai grandly celebrated the Chithirai festival, devotees thronged streets, got darshan of deities Meenakshi, Sokkanathar, and Kallazhagar: “Govinda” “Hara Hara” chants reverberated in Madurai with pomp

- "Untold Love Story": Queen Rudabai tricked Mahmud Begada by agreeing to marriage only after the completion of the Adalaj Stepwell, a cherished project started by her late husband, King Veer Singh, and then sacrificed her life to protect its sanctity

- "Purify your hearts with the water of love of motherland in national temple, and promise that millions will not remain untouchables, but brothers and sisters": Swami Shraddhanand, who awoke Hindu consciousness

- Hindu Survival: What Is Needed To Be Done?

- Maa Annapurna returns to India after 107 years of exile in Canada: Murti will be installed at Kashi Vishwanath Mandir in Varanasi

- The Spiritual Centre of Hindu Society - Defence of Hindu Society

- Now Bharatwasi can see 3D visualization of Ram Mandir construction progress in detail through a video released by Shri Ram Janmabhoomi Teerth Kshetra Trust: Ayodhya

- The Basis of Universal Spirituality - Defence of Hindu Society

- Sanãtana Dharma Versus Prophetic Creeds - Defence of Hindu Society

- "Neglect will drive a noble mind to depart for another land": Brilliant mind - Dr Subhash Mukhopadhyay who created India's first and world's second test tube baby 'Durga' in 1978 with the help of some general equipment and refrigerator was punished for it

- Indonesia: Sukmawati Sukarnoputri, daughter of Indonesia's first president becomes a Hindu leaving Islam