Sanatan Articles

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

Winston Churchill's hate for Indians caused millions of deaths: A villainous supremacist

Within his homeland, Winston Churchill’s colossal contribution to saving his people from Hitler eclipses all else, and he is widely regarded as the greatest Briton of all time. But, could a man applauded for his courage in standing up to Adolf Hitler have had such contempt for another race that he did not change policies that led to starvation and death of at least three million? The man was Sir Winston Churchill and the famine that killed millions was in India in 1943.

Sir Winston Churchill, twice British Prime Minister, made numerous statements on race throughout his life before, during, and after his career in British politics. Assessment's on Churchill's legacy have traditionally focused on his leadership of the British people during the Second World War. However, in the 21st century, some critics have argued that evaluations of Churchill's legacy must include his imperialist and racist views, which they alleged played a part in various decisions he made while in office; these include his response to the Bengal famine of 1943. He consistently exhibited a "romanticised view" of both the British Empire and the reigning British monarchy, especially of Elizabeth II during his last term as premier.

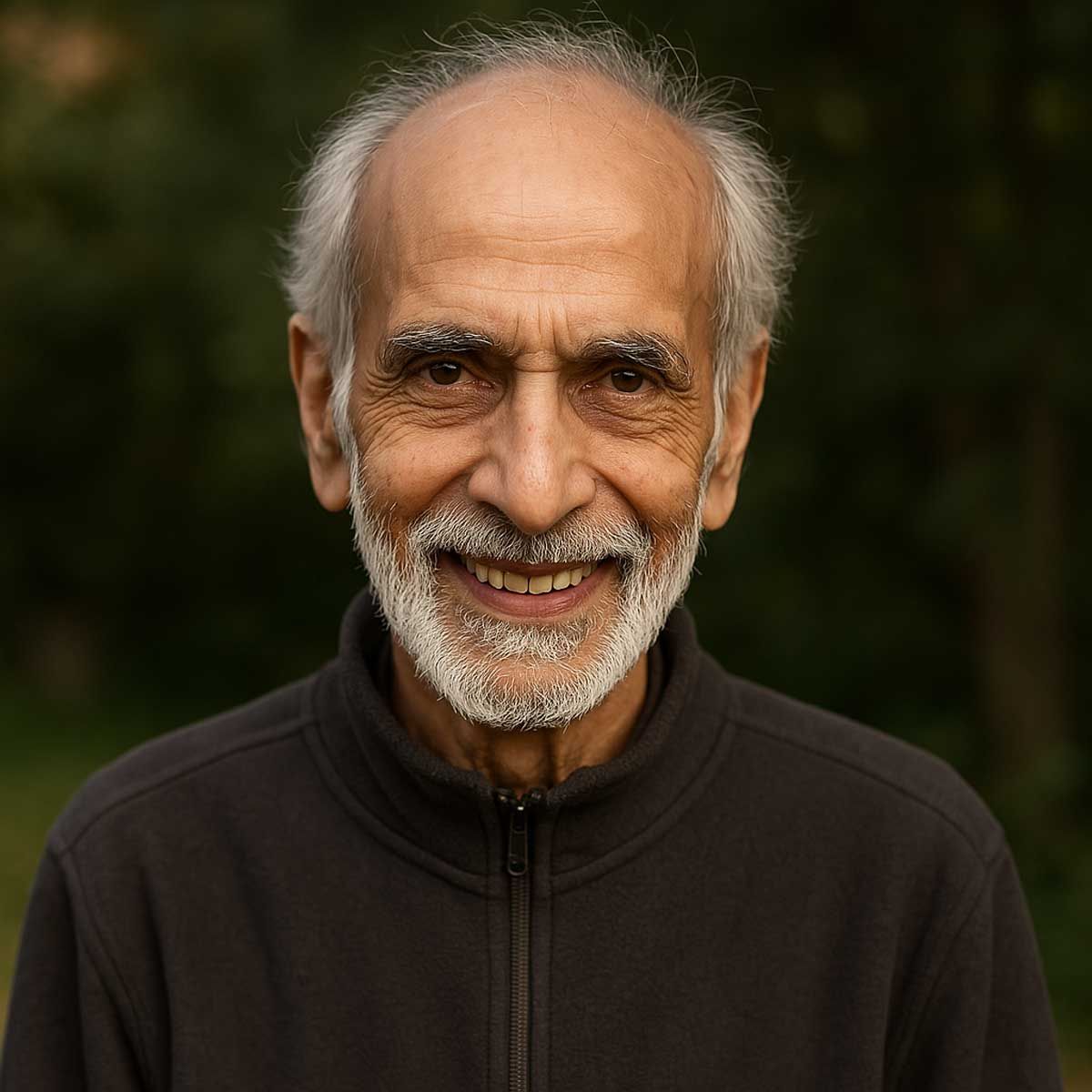

Winston Churchill, British Prime Minister |

A Hatred for Hindus

Historian John Charmley has written that Churchill viewed British domination around the globe, such as the British Empire, as a natural consequence of social Darwinism. Charmley argued that similar to many of Churchill's contemporaries, he held a hierarchical perspective on race, believing white Protestant Christians to be at the top of this hierarchy, and white Catholics beneath them, while Indians were higher on this hierarchy than Black Africans. Charmley adds the he believes that Churchill saw himself and Britain as being the winners in a social Darwinian hierarchy. As Richard Toye notes, such racism was common in Churchill’s England.

In 1955, Churchill expressed his support for the slogan "Keep England White" with regards to immigration from the West Indies.

Churchill often made disparaging comments about Indians, particularly in private conversation. At one point, he explicitly told his Secretary of State for India, Leo Amery, that he "hated Indians" and considered them "a beastly people with a beastly religion".

John Charmley has argued that Churchill's denigration of Mahatma Gandhi in the early 1930s contributed to fellow British Conservatives' dismissal of his early warnings about the rise of Adolf Hitler. Churchill's comments on Indians – as well as his views on race as a whole – were judged by his contemporaries within the Conservative Party to be extreme. Churchill's personal doctor, Lord Moran, commented at one point that, in regards to other races, "Winston thinks only of the colour of their skin."

In February 1945 Winston Churchill had dinner with his secretary John Colville and Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris. Colville’s diary records that: ‘The PM said the Hindus were a foul race ... and he wished Bert Harris could send some of his surplus bombers to destroy them.’

Churchill had expressed contempt for Hindus before. Three years earlier he had told Ivan Mikhailovich Maisky, the Soviet ambassador in London, that, should the British be forced to leave India: ‘Eventually, the Moslems will become master, because they are warriors, while the Hindus are windbags.’ Churchill opined that, while Hindus were experts at building ‘castles in the air’, ‘when something must be decided on quickly, implemented, executed – here the Hindus say “pass”. Here they immediately reveal their internal flabbiness.’

In his youth Churchill had considered converting to Islam. He had always admired the Muslim faith and, during the war, lied to Roosevelt that the majority of the Allies’ Indian soldiers were Muslim. In fact, the majority were Hindu.

Churchill’s views were influenced by Beverley Nichols’ 1944 book Verdict on India. Nichols, a Nazi sympathiser, wrote the book as propaganda to discredit the Indian National Congress, which was then agitating against British rule. Nichols saw his mission as demolishing the Hindu cause.

Hindu art and music, he wrote, was ‘to most Europeans … not only quite incomprehensible but actively repulsive’. Gandhi, then in a British jail, was featured in a chapter entitled ‘Heil Hindu’ and Hindus were described as worse than the Nazis:

Congress is the only 100 per cent, full blooded, uncompromising example of undiluted Fascism in the modern world … Just as every Nazi is a superman, so every Brahmin is ‘Bhudeva’, which means ‘God on earth’. And Congress is, of course, a predominantly Brahmin organisation ... The resemblances between Gandhi and Hitler are, of course, legion.

Churchill, recommending the book to his wife, wrote: ‘I think you would do well to read it ... It certainly shows the Hindu in his true character.’

Yet Churchill was not the first to want to destroy Hinduism. For more than 200 years, hatred of Hindus was the default position of many influential people in Britain. The man who set this agenda was James Mill, whose 1817 text book The History of British India, became the most important at Haileybury College, where the civil servants of the East India Company were taught. ‘The Hindus’, Mills wrote, ‘are full of dissimulation and falsehood, the universal concomitants of oppression. The vices of falsehood, indeed they carry to a height almost unexampled among the other races of men.’ As for religion, Mill wrote, ‘No people … have ever drawn a more gross and disgusting picture of the universe than what is presented in the writings of the Hindus.’ Mill had no such problem with Islam: ‘Very few words are required; because the superiority of the Mahomedans in respect of religion is beyond all dispute.’

Winston Churchill With His Chiefs of Staff in the Garden of No 10 Downing Street London |

Mill also felt that Muslims believed in the ‘natural equality of mankind’, whereas the Hindu performance of religious ceremonies was ‘to the last degree contemptible and absurd, very often tormenting and detestable’. For Mill, the greatest contrast was in the behaviour of Hindus and Muslims. ‘In truth the Hindu, like the eunuch, excels in the qualities of a slave … the Mahomedan is more manly.’

Thomas Babington Macaulay, who made the decision that Indians should be taught in English rather than their native languages, described Mill’s history as ‘the greatest historical work which has appeared in our language since that of Gibbon’. Like Mill, Macaulay also fulminated against Hinduism saying: ‘In no part of the world has a religion ever existed more unfavourable to the moral and intellectual health of our race.’ The Hindus had ‘an absurd system of physics, an absurd geography, and absurd astronomy’. Nor were they any better at art. ‘Through the whole of the Hindoo pantheon you will look in vain for anything resembling those beautiful and majestic forms which stood in the shrines of ancient Greece. All is hideous, and grotesque and ignoble.’ In contrast Macaulay admired Islam, calling it a faith belonging to a ‘better family’, related as it was to Christianity.

Until well into the 19th century the British continued to acquire territories but were, in effect, acting as leaseholders, accepting the Mughal Emperor as the freeholder of India. The various courts of British India basically followed Mughal law. A Muslim law officer delivered a fatwa, declaring whether the accused was guilty and what the punishment should be. The Englishman sitting next to him then passed sentence. As Sir George Campbell wrote in 1852: ‘The hidden substructure on which this [whole system] rests is this Mahommedan law; take which away, and we should have no definition of, or authority, for punishing many of the most common crimes.’ It was even common for robbers in British-run Bengal to have a foot chopped off.

After the revolt of 1857 there were calls to eradicate Hinduism. The Baptist preacher Charles Spurgeon told a congregation of 25,000 at Crystal Palace that ‘such a religion as the religion of the Hindoo, the Indian government were bound, as in the sight of God, to put down with all the strength of their hand’. And even after the British had left India, Hinduphobia persisted. Francis Tuker, who spent 33 years in the Indian Army, retired as head of Eastern Command in 1950. Writing of independent India, he feared the advance of Communism there: ‘The Iron Curtain … clanks down between Hinduism and all other systems and religions.’ Hindu India was entering a precarious phase, when it might swap its gods for another. ‘Its religion, which is to a great extent superstition and formalism, is breaking down … Communism will fill the void left by the Hindu religion. It seemed to some of us very necessary to place Islam between Russian Communism and Hindusthan.’

In 1943, India, then still a British possession, experienced a disastrous famine in the north-eastern region of Bengal - sparked by the Japanese occupation of Burma the year before.

Madhusree Mukerjee, who has served on the editorial board of Scientific America and is the author of The Land of the Naked People, took eight years to reveal Churchill's complicity in the Bengal famine in her new book Churchill's Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India during World War II.

The book, published in America, received solid reviews in India and the United Kingdom.

'Churchill's dislike of India and Indians has been known to scholars,' wrote historian Ramachandra Guha, author of India after Gandhi. 'But now, in Churchill's Secret War, we have, for the first time, definitive evidence of how a great man's prejudices contributed to one of the most deadly famines in modern history.'

'The Churchill industry, more interested in the great man's dentures than in his war crimes, has managed to keep this appalling story fairly quiet The Churchill industry has always denied that their idol could have done anything to relieve the Bengal famine. Shipping, they claim, was scarce and it just wasn't possible to send food to Bengal,' Chandak Sengoopta, who teaches history at London's Birkbeck College, wrote in The Independent "Mukerjee nails those "terminological inexactitudes" with precision Churchill, [his beloved advisor, physicist Frederick Alexander] Lindemann and their close associates simply did not consider Indian lives worth saving.'

"I have been concerned with hunger for many years," said Mukerjee, from her home near Frankfurt, Germany. "I began looking at hunger and poverty in India many years ago and came to view the role played by famine. I have no background in history; I had to look at not only history, but also the economics of colonialism. I read the works of many eminent scholars, including B N Bhatia, who has written extensively on famines in India. But many questions were left unanswered in the books and journals I studied."

She was worried that the Bengal famine was always studied as a local issue. "Nobody had really studied the complicity of outsiders [the imperial British power], and how the shipping constraints during World War II added to the situation. I had to dig deep into the history of wartime shipping and I came across information as to how Churchill changed the shipping routes around the Indian Ocean," she said.

The Second World War saw India fast becoming a creditor to London, since it provided materials which could not be produced at home. This, however, was achieved by the government through increasing money supply in India, leading to inflation. The best Indian troops were fighting in the Mediterranean, since high command had it that Japan did not stand a chance at against the Royal Navy in the Indian Ocean. Yet, Singapore fell in 1942, initiating a swift Japanese advance into Burma. In response, the British followed a “scorched earth policy”; destroying industrial, and most importantly, the transportation infrastructure, along the coastal region of Bengal, which was the cornerstone of its riverine economy.

Since the crop had been harvested, food supplies were also tightened, with the government willing to pay any amount to keep “the war effort” going in Calcutta; feeding industrial workers and the army, a large part of which was foreign. After all Calcutta was the link to China, a route through which the Japanese had to be combated. But such expenditure on crop only inflated prices further. At a time when the primary supplies of rice to Bengal stopped, because Burma was conquered, not only were prices rising, but Bengal‟s crop was being exported to other places – deemed to be of greater strategic import – to substitute for the crop that was being got from South East Asia. Having imported 296, 000 tons of rice in 1941, it would export 185, 000 tons in 1942.

Amidst warnings of famine and impending famine, Churchill decided to cut its Indian Ocean shipping by more than half in January 1943, even while stockpiling of the precious commodity in England gathered pace. London had food supplies well over what was deemed essential and necessary, but all the same let it be known that it was in dire straits; in such a context the Government of India found it impossible to press for grain, in spite of the famine and slowly encircling devastation.

Using records released in 2006, Mukerjee makes a convincing case that grain was being stockpiled in England, in the anticipation of grain scarcity/high prices in a post-war situation. Its more immediate function was to give strategic and operational flexibility. One argument that speaks of the famine being "understandable" in the midst of wartime because of inherent shipping requirements doesn't account for the fact that in 1943, there was in the words of one contemporary, a “shipping glut”.

The German U-boats had been defeated and America was producing ships well beyond what were required. Further reasons for the resistance towards sending grain to the starving in Bengal included the anticipated need of grain in the Balkans (70 to a 100,000 tons) once these peoples would be liberated. This was perhaps an ominous reminder of the fact that earlier in the Atlantic Charter, Churchill had insisted on disqualifying the conquered peoples of Asia from those of Europe who were deemed as entitled to freedom. Discrimination couldn‟t have a clearer sheen.

"[The War Cabinet] ordered the build-up of a stockpile of wheat for feeding European civilians after they had been liberated. So 170,000 tons of Australian wheat bypassed starving India - destined not for consumption but for storage," she said upon release of the book in 2010.

|

1942–1944: Refusal of imports

Beginning as early as December 1942, high-ranking government officials and military officers (including John Herbert, the Governor of Bengal; Viceroy Linlithgow; Leo Amery the Secretary of State for India; General Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief of British forces in India, and Admiral Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Commander of South-East Asia) began requesting food imports for India through Government and military channels, but for months these requests were either rejected or reduced to a fraction of the original amount by Churchill's War Cabinet.

The colony was also not permitted to spend its own sterling reserves, or even use its own ships, to import food. Although Viceroy Linlithgow appealed for imports from mid-December 1942, he did so on the understanding that the military would be given preference over civilians. The Secretary of State for India, Leo Amery, was on one side of a cycle of requests for food aid and subsequent refusals from the British War Cabinet that continued through 1943 and into 1944. Amery did not mention worsening conditions in the countryside, stressing that Calcutta's industries must be fed or its workers would return to the countryside. Rather than meeting this request, the UK promised a relatively small amount of wheat that was specifically intended for western India (that is, not for Bengal) in exchange for an increase in rice exports from Bengal to Ceylon.

The tone of Linlithgow's warnings to Amery grew increasingly serious over the first half of 1943, as did Amery's requests to the War Cabinet; on 4 August 1943 Amery noted the spread of famine, and specifically stressed the effect upon Calcutta and the potential effect on the morale of European troops. The cabinet again offered only a relatively small amount, explicitly referring to it as a token shipment. The explanation generally offered for the refusals included insufficient shipping, particularly in light of Allied plans to invade Normandy. The Cabinet also refused offers of food shipments from several different nations.

When such shipments did begin to increase modestly in late 1943, the transport and storage facilities were understaffed and inadequate. When Viscount Archibald Wavell replaced Linlithgow as Viceroy in the latter half of 1943, he too began a series of exasperated demands to the War Cabinet for very large quantities of grain. His requests were again repeatedly denied, causing him to decry the current crisis as "one of the greatest disasters that has befallen any people under British rule, and [the] damage to our reputation both among Indians and foreigners in India is incalculable". Churchill wrote to Franklin D. Roosevelt at the end of April 1944 asking for aid from the United States in shipping wheat in from Australia, but Roosevelt replied apologetically on 1 June that he was "unable on military grounds to consent to the diversion of shipping".

Lizzie Collingham holds the massive global dislocations of supplies caused by World War II virtually guaranteed that hunger would occur somewhere in the world, yet Churchill's animosity and perhaps racism toward Indians decided the exact location where famine would fall. Similarly, Madhusree Mukerjee makes a stark accusation: "The War Cabinet's shipping assignments made in August 1943, shortly after Amery had pleaded for famine relief, show Australian wheat flour travelling to Ceylon, the Middle East, and Southern Africa – everywhere in the Indian Ocean but to India. Those assignments show a will to punish."

Churchill even appeared to blame the Indians for the famine, claiming they "breed like rabbits".

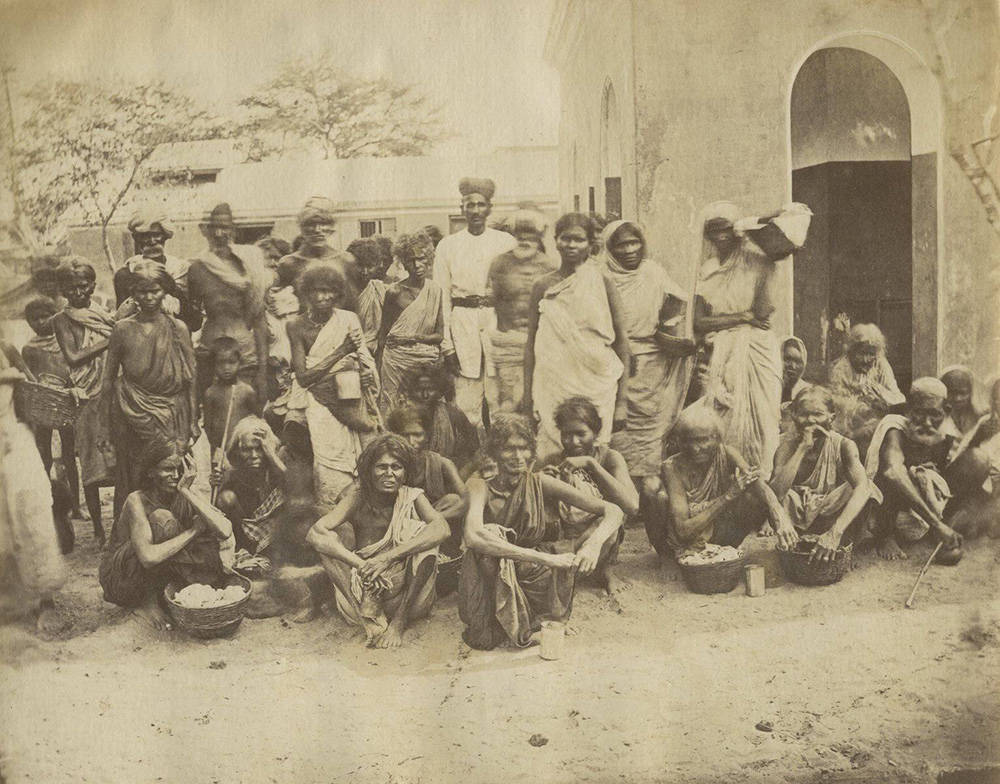

Mukerjee portrays the denial of grain and the ravaging of the countryside in heart rendering detail. Speculating on why there were no riots or violence, Mukerjee says that people were literally too weak to resist. It was not uncommon to see the dying splattering the streets of Calcutta, or them collapsing at a mere shove from a shopkeeper protecting his grain. Women from rural areas survived through large scale prostitution networks in the city, servicing the armies in particular. The visibility of the famine was for all to see and yet this did not provoke any measure from Britain.

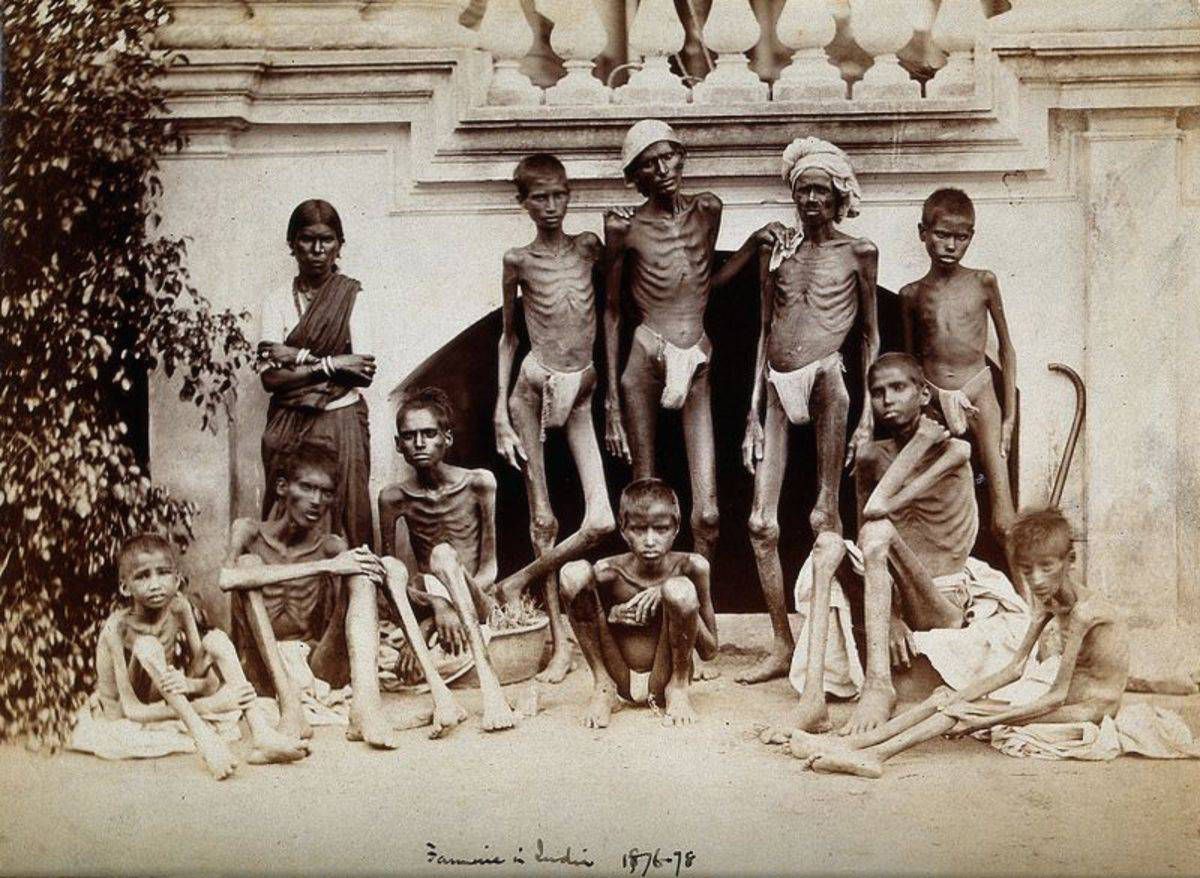

A family on the sidewalk in Calcutta during the Bengal famine of 1943 |

Not only this, since now the news of the famine was widespread, other independent bodies such as the Combined Food Board, the Board of Economic Welfare, and countries such as Canada, were actually prevented from lending a helping hand, by London, using the rationale of it being a waste of shipping space. That 9000 tons of rice from Brazil was on its way to Ceylon, shiploads of wheat were circumnavigating India on their way to the “Balkan stockpile”, and similar shiploads carried wheat for Britain from Argentina, when Britain had already more than enough wheat, would have to be cynically scoffed at as non sequitur. While proposals were being made to set up the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration whose agenda was to “provide relief to victims of war in any area under the control of the United Nations” the Government of India actively prevented the inclusion of starving Bengal, even while India was made to contribute in funds.

At the same time, London imported 4 million tons of wheat grain, allowing her stock pile to reach 18.5 million tons, in view of a brave new post-war world. Only in November 43, did Britain finally authorize 130,000 tons of Barley and 80,000 tons of wheat, for a region with a population of 14 million more than Britain. This was a protracted, cynical, brutal but certainly not secret, war.

The British using air power against civilians during the Quit India movement – not the first time since air power was also used in the Punjab in 1919 – and the "liberated zones" are portrayed through the lives of certain characters such as Sushil Dhara. As a "technique" this is not isolated, for Mukerjee gives us vivid pictures of key actors, such as Winston Churchill, Leopold Amery, Clive Branson (a soldier whose diaries are marvelously put to effect) and Lord Cherwell. A more suppressed – though unmistakable – thread is the comparison with Nazi Germany and the way ideology is institutionally enacted.

In the late 19 century, in the context of India‟s devastating famines, Churchill had somberly commented “a philosopher may watch unmoved the destruction of some of those superfluous millions, whose life must of necessity be destitute of pleasure”; he was to quickly blunt his prose later, calling Indians, “a beastly people with a beastly religion”.

The same 19th century Empire had sat up famine relief camps where rations were less than those that would characterize the concentration camps of Buchenwald, as Mike Davis has written, and whose work can be read as a prequel to the present one; such economy would be repeated in 1943-44 when rations finally started trickling in, as Mukerjee tells us.

Churchill‟s most trusted advisor, Lord Cherwell, who played an important role in denying grain to Bengal, was a strong believer in eugenics and racial superiority. The way belief took on horrific historical import, across the antagonists of the Second World War, is something Mukerjee raises through an incisive study of a "case‟, opening a window into the entangled histories of imperialism, democracy and totalitarianism.

Leo Amery likened Churchill's understanding of India's problems to King George III's apathy for the Americas. In his private diaries, Amery wrote "on the subject of India, Winston is not quite sane" and that he did not "see much difference between [Churchill's] outlook and Hitler's".

|

Famine, disease, and the death toll

An estimated 3 million Bengalis died, out of a population of 60.3 million. However, contemporary mortality statistics were to some degree under-recorded, particularly for the rural areas, where data collecting and reporting was rudimentary even in normal times. Thus, many of those who died or migrated were unreported. The principal causes of death also changed as the famine progressed in two waves.

The two waves – starvation and disease – also interacted and amplified one another, increasing the excess mortality. Widespread starvation and malnutrition first compromised immune systems, and reduced resistance to disease led to death by opportunistic infections. Second, the social disruption and dismal conditions caused by a cascading breakdown of social systems brought mass migration, overcrowding, poor sanitation, poor water quality and waste disposal, increased vermin, and unburied dead. All of these factors are closely associated with the increased spread of infectious disease.

|

Social disruption

The famine fell hardest on the rural poor. As the distress continued, families adopted increasingly desperate means for survival. First, they reduced their food intake and began to sell jewellery, ornaments, and smaller items of personal property. As expenses for food or burials became more urgent, the items sold became larger and less replaceable. Eventually, families disintegrated; men sold their small farms and left home to look for work or to join the army, and women and children became homeless migrants, often travelling to Calcutta or another large city in search of organised relief:

Husbands deserted wives and wives husbands; elderly dependents were left behind in the villages; babies and young children were sometimes abandoned. According to a survey carried out in Calcutta during the latter half of 1943, some breaking up of the family had occurred in about half the destitute population which reached the city.

Mother with child on a Calcutta street. Bengal famine 1943 |

Cloth famine

As a further consequence of the crisis, a "cloth famine" left the poorest in Bengal clothed in scraps or naked through the winter. The British military consumed nearly all the textiles produced in India by purchasing Indian-made boots, parachutes, uniforms, blankets, and other goods at heavily discounted rates. India produced 600,000 miles of cotton fabric during the war, from which it made two million parachutes and 415 million items of military clothing. It exported 177 million yards of cotton in 1938–1939 and 819 million in 1942–1943. The country's production of silk, wool and leather was also used up by the military.

Swami Sambudhanand, President of the Ramakrishna Mission in Bombay, stated in July 1943:

The robbing of graveyards for clothes, disrobing of men and women in out of way places for clothes ... and minor riotings here and there have been reported. Stray news has also come that women have committed suicide for want of cloth ... Thousands of men and women ... cannot go out to attend their usual work outside for want of a piece of cloth to wrap round their loins.

Many women "took to staying inside a room all day long, emerging only when it was [their] turn to wear the single fragment of cloth shared with female relatives".

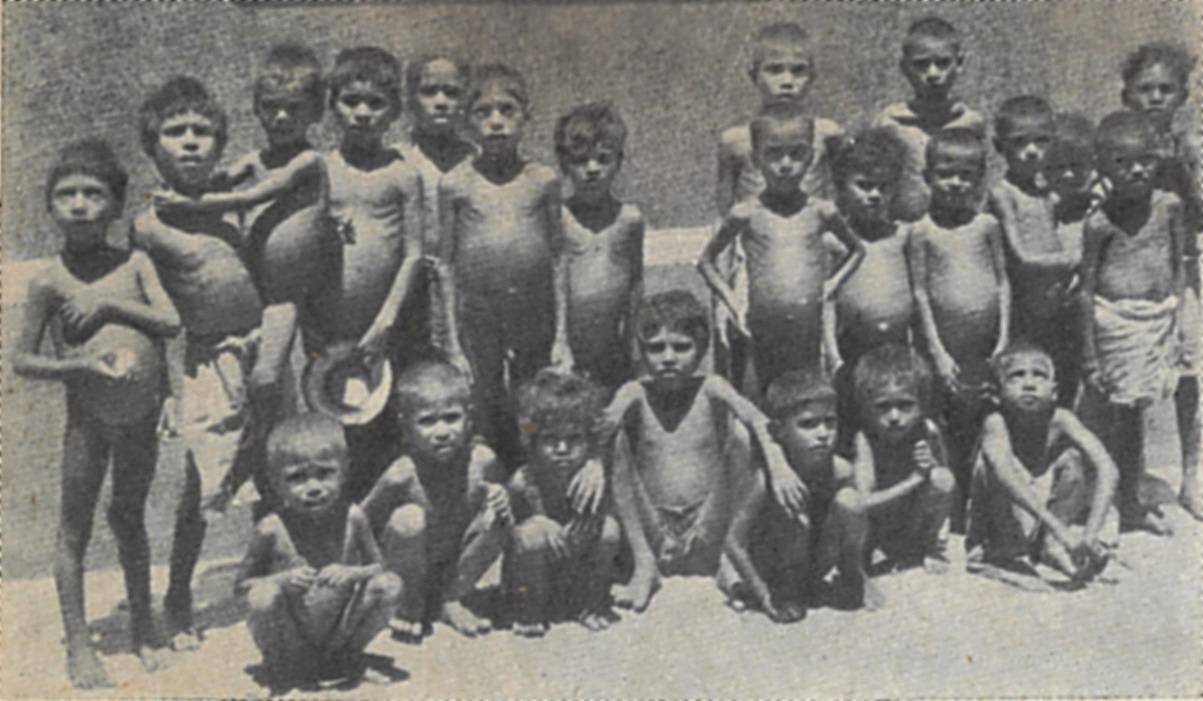

Orphans who survived the famine |

Exploitation of women and children

One of the classic effects of famine is that it intensifies the exploitation of women; the sale of women and girls, for example, tends to increase. The sexual exploitation of poor, rural, lower-caste and tribal women by the jotedars had been difficult to escape even before the crisis. In the wake of the cyclone and later famine, many women lost or sold all their possessions, and lost a male guardian due to abandonment or death. Those who migrated to Calcutta frequently had only begging or prostitution available as strategies for survival; often regular meals were the only payment.

Tarakchandra Das suggests that a large proportion of the girls aged 15 and younger who migrated to Calcutta during the famine disappeared into brothels; in late 1943, entire boatloads of girls for sale were reported in ports of East Bengal. Girls were also prostituted to soldiers, with boys acting as pimps. Families sent their young girls to wealthy landowners overnight in exchange for very small amounts of money or rice, or sold them outright into prostitution; girls were sometimes enticed with sweet treats and kidnapped by pimps. Very often, these girls lived in constant fear of injury or death, but the brothels were their sole means of survival, or they were unable to escape. Women who had been sexually exploited could not later expect any social acceptance or a return to their home or family. Bina Agarwal writes that such women became permanent outcastes in a society that highly values female chastity, rejected by both their birth family and husband's family.

An unknown number of children, some tens of thousands, were orphaned. Many others were abandoned, sometimes by the roadside or at orphanages, or sold for as much as two maunds (one maund was roughly equal to 37 kilograms), or as little as one seer (1 kilogram) of unhusked rice, or for trifling amounts of cash. Sometimes they were purchased as household servants, where they would "grow up as little better than domestic slaves". They were also purchased by sexual predators. Altogether, according to Greenough, the victimisation and exploitation of these women and children was an immense social cost of the famine.

|

Economic and political effects

The famine's aftermath greatly accelerated pre-existing socioeconomic processes leading to poverty and income inequality, severely disrupted important elements of Bengal's economy and social fabric, and ruined millions of families.

"It was soon obvious to the bureaucrats in New Delhi and the provinces, as well as the GHQ (India)," wrote Sanjoy Bhattacharya, "that the disruption caused by these short-term policies – and the political capital being made out of their effects – would necessarily lead to a situation where major constitutional concessions, leading to the dissolution of the Raj, would be unavoidable."

The denial of boats alarmed the public; the resulting dispute was one point that helped to shape the "Quit India" movement of 1942 and harden the War Cabinet's response. An Indian National Congress (INC) resolution sharply decrying the destruction of boats and seizure of homes was considered treasonous by Churchill's War Cabinet, and was instrumental in the later arrest of the INC's top leadership.

A related argument, present since the days of the famine but expressed at length by Madhusree Mukerjee, accuses key figures in the British government (particularly Prime Minister Winston Churchill) of genuine antipathy toward Indians and Indian independence, an antipathy arising mainly from a desire to protect imperialist privilege but tinged also with racist undertones. This is attributed to British anger over widespread Bengali nationalist sentiment and the perceived treachery of the violent Quit India uprising.

One man's hatred for Indians affected millions of lives

Winston Churchill was often said to be permanently mid-Victorian, although being born in 1874 made him a late Victorian. He was bitterly determined to hold on to India; he hated Indians, and intended that they remain subjects for all time. He had expressed his disgust at 'a half naked fakir parleying with the British' when Mahatma Gandhi attended the Round Table Conference. Again, as the British PM, he refused to talk about granting India independence, saying he had not 'become His Majesty's first minister to preside over the liquidation of the British empire'.

With sources ranging from official documents to first-hand accounts of the Bengal famine, Madhusree Mukerjee brings out the consequences for India, and thereby for hundreds of millions of people.

Major policies were designed to exploit the divisions in Indian society — whatever that meant — and the greatest weaknesses in a culture which Amitav Ghosh has described as being informed by a monumental inwardness, a property which renders those who possess it ill-equipped to read an outsider's intentions. The double-dealing before Plassey is well known, but the colonials often used a central indeterminacy in their Indian subjects' conceptions of who was, or was not, an Indian to undermine any serious challenge to foreign rule.

“This was a unique famine, caused by policy failure instead of any monsoon failure,” said Vimal Mishra, the lead researcher and an associate professor at the Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar.

|

On August 22, 1943, a newspaper printed close-up photographs of young children pointing rib cages and stick-like legs. The statesman started publishing editorials for spreading famine. They wrote, but nothing came out of it.

The problem was that Winston disliked Indians so much that he saw nothing but a waste of food shipments if sent to India. By the end of 1944, the worst side of famine was exposed, which triggered the end of the British government. Solely Churchill and his policies were responsible for this great catastrophe. His antipathy towards India made the Indians go through such frightful conditions.

The nauseating racism of this man is fully evident in this disgusting statement that he made before the Peel's Commission -

I do not agree that the dog in a manger has the final right to the manger even though he may have lain there for a very long time. I do not admit that right. I do not admit for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race, a more worldly wise race to put it that way, has come in and taken their place.

All in all, Churchill was far more damaging to India and to Indians than Hitler ever could be. Hitler's effect on India was the death of the Indian soldiers who fought for the British. Churchill's effect on India was the painful death of many civilians and the holocaust of partition that followed the shameful and uncoordinated flight of the Brits which could have been averted had Churchill seen the writing on the wall and negotiated for a logical withdrawal of the British well in advance.

References:

Madhusree Mukerjee's book on Winston Churchill bares his dark side, reports Arthur J Pais

Rediff.com

Historytoday.com

wikipedia.org

Kreately.in

Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India during World War II - Madhushree Mukerjee - Biblio in January-February 2011

BBC

medium.com - Krishh

thehindu.com - Arvind Sivaramakrishnan

Quora.com - Why is Winston Churchill hated in India

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/india/7991820/Winston-Churchill-blamed-for-1m-deaths-in-India-famine.html

https://owlcation.com/humanities/The-1943-Famine-in-Bengal

https://qph.fs.quoracdn.net

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- On 16th Aug 1946, during Ramzan's 18th day, Direct Action Day aimed to provoke Muslims by mirroring Prophet Muhammad's victory at Badr, Gopal 'Patha', the Lion of Bengal, heroically saved Bengali Hindus & Calcutta from a planned genocide, altering history

- Tragedy or Drama: Mufti Mohammad Sayeed's daughter Rubaiya abduction led to free five most notorious terrorists

- Prophecies of Jogendra Nath Mandal getting real after seventy years of his return from Pakistan

- Tipu Sultan remembered as killer of Brahmins and demolisher of temples in many villages of Tamil Nadu: a freedom fighter or Islamic bigot?

- Ban this book "Hindu View of Christianity and Islam" by Ram Swarup - Freedom of Expression

- Narasimha Rao govt brought places of Worship Act as a hurdle in reclaiming ancient Hindu heritage destroyed by Muslim invaders

- Why Hindu-Sikh genocide of Mirpur in 1947 ignored? Why inhuman crimes of Radical Islamists always hidden in India?

- Hindus documented massacres for 1000s of years: Incomplete but indicative History of Attacks on India from 636 AD

- Gandhi corrupted the original Hindu bhajan ‘Raghupati Raghav Raja Ram’ by including ‘Allah’

- Godse's speech and analysis of fanaticism of Gandhi: Hindus should never be angry against Muslims

- Operation Polo: When India annexed Hyderabad from the Nizam and Razakars, the suppression of Hindus and the role of Nehru

- Soft-conditioning of Hindu minds to normalize grooming jihad in Bengali TV serial ‘Khorkuto’

- Why India’s temples must be freed from government control

- The United Front of Hostile Forces - Hindu Society Under Siege

- Land Jihad being carried out by Waqf Board much more dangerous than Love Jihad; Hindus need to fight this